Before the Battle of London and Pearl Harbor, some of the biggest campus concerns included funding a new student activities building and a debate — through letters to this magazine — over whether the University should continue calling itself the Spiders or opt for a Confederate mascot to throwback to the city’s role during the Civil War. (Thankfully, wisdom and the Spiders prevailed.)

Early campus attitudes to the war were somewhat isolationist, as was much of the country. On Sept. 15, 1939, The Collegian began printing “AMERICA MUST STAY OUT OF WAR!” above its nameplate and announced it would keep that statement there through the duration of the conflict in Europe. In that same issue, the editorial board penned an isolationist jeremiad denouncing U.S. involvement in Europe. A year later, the statement disappeared. The federal government had instituted the draft, and the Battle of London had helped shape public attitudes about the country’s inevitable entry into the conflict.

By the spring of 1941, the “Undergraduate Slant,” a regular Alumni Bulletin feature written by students, reported that some 250 students, faculty, and staff had registered for the draft. “‘Help Britain at all costs’ is the dominant attitude, and the progress of the war is daily charted in the between-class groups gathered on the grass these warm, spring days,” wrote Paul Saunier Jr., R’40. “War or peace, the young Spiders are taking the world in stride.”

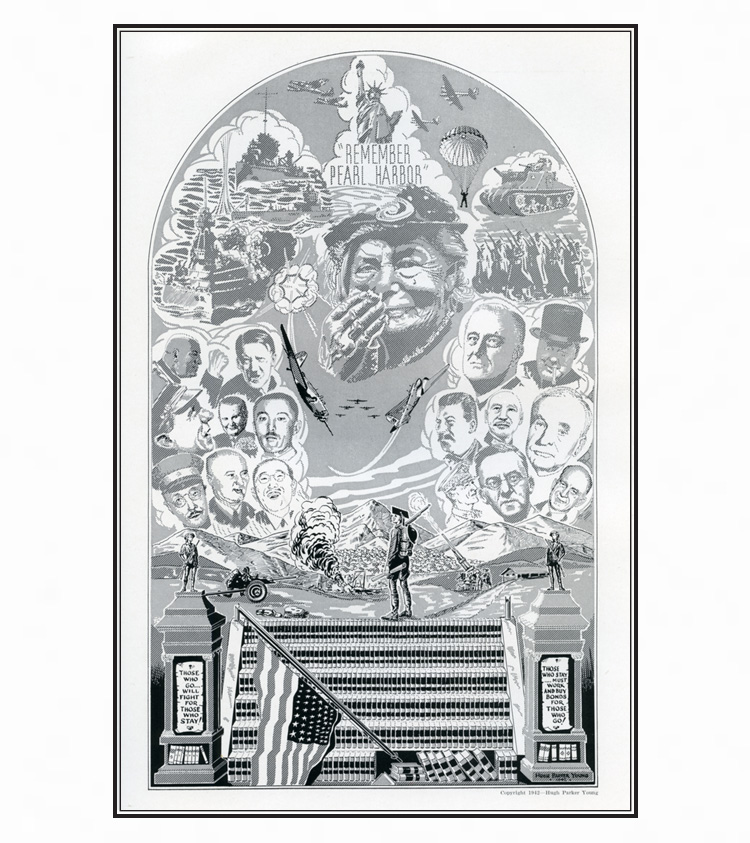

Then came Pearl Harbor, where at least four alumni were stationed during the attack, and the stakes became abundantly clear. Campus, like the country, transformed to meet the tasks ahead. Suddenly, the young men who had been coxswains on the UR crew team now took charge of much bigger tasks on much bigger boats. Westhampton students planted victory gardens and took to the rooftops to watch the skies for enemy aircraft. Class notes came through censors from abroad. And one of our own received the Medal of Honor for his valor in Italy.

But this overwhelmingly patriotic response came at a cost to UR and many universities as they struggled with decreasing enrollment and uncertain finances. In the end, the very wartime needs that threatened UR would shore it up in the short term and for generations.

Classes have taken on a new value since the war. Instead of studying for grades or parents, they are studying for that time when such knowledge will become dynamite in their hands.

SOMEWHERE OVER THERE

On a cold, crisp February morning in 1943, President Frederic Boatwright, along with students and family members, helped see off 49 men called up from the Army Reserve. The 49ers, as they were nicknamed, left on a streetcar to begin their journey to Fort Meade, Md. The local newspaper pointed out the sobriquet, given because of their number, suited the young men well since, in a way, they were also pioneers — “the first of the college reserves to forsake the classroom for the training field and the eventual field of battle.”

“From the far-flung battlefields have come word of heroic exploits by University of Richmond alumni in the uniforms of the Army, the Navy, and the Marine Corps,” begins the coverage of the war by the Alumni Bulletin, as this magazine was then called. Replacing stories about math and biology at the college were lists of promotions and accounts of more lives lost in the struggle against the Axis.

A regular feature — called “Passed By Censor” — began appearing in the magazine and offered bits of everyday life at the warfront. The name came from the stamp applied to mail as it was screened to prevent any “loose lips sink ships” situations. Many of the letters express the surprise of men abroad who met fellow Spiders in the most unexpected corners of the globe. Some expressed the mundane life of being stuck on a ship.

“You didn’t get off the ship very much,” says Bill Magee, R’48, who served on a destroyer in the Pacific. “The big deal was to be able to come into some island base that was established and have a baseball game and beer and hot dogs.”

The experience for many was incredibly harrowing. Jimmy Boehling, R’48, was drafted into the Army Air Force and shipped off to Europe. He was the navigator for a B-17 combat mission over occupied Germany when he noticed the plane stalled. He tried alerting the copilots and the togglier to no avail, and eventually decided he needed to bail.

“So I took my parachute off the table — I forgot to hook to the right side — pushed the door open with my shoulder, and rolled out headfirst into the slipstream.” Boehling said.

“I never saw the airplane again, but I heard an enormous crashing sound.”

Boehling floated down into a field 10 minutes later. A German farmer largely ignored him and a group of school boys on bikes helped get him to the road, where a French lorry and then an American jeep eventually got him to a castle being used as a radar station. He was reassigned to a new crew and given a week of leave for rehabilitation back in London. Just before he was about to ship out to the Pacific Theater, the war in Japan ended with the atomic bombs.

“I was quite relieved of course,” says Boehling, who now lives in Richmond’s Fan District. “But I was prepared to go against Japan.”

Had the war not ended, Boehling would have begun flying on a B-29 bomber over Japan, a prospect that didn’t sit well with him.

“I didn’t know at the time of the massive firebombing that they did against Japan,” Boehling says. “It was just saturation bombing. And I would not have liked to do that. I didn’t mind deploying against military targets, but not against civilians. Fortunately, I never had to.”

All told, around 1,400 alumni and former students served in uniform. At least 60 died in service, including one woman, Elizabeth Seay, W’33, a member of the U.S. Navy’s WAVES division for women. Ernest Dervishian, L’38, would receive the Congressional Medal of Honor for “conspicuous gallantry.”

ON THE HOME FRONT

At the University, life had begun changing in the years before the U.S. entered the war. “‘On borrowed time’ sums up the attitude of University of Richmond students today,” wrote the late Guy Fridell, R’43, in his last act before being drafted into the U.S. Army Medical Corps. “Those students privileged to remain in school feel that they must make the most of their opportunities. Classes have taken on a new value since the war. Instead of studying for grades or parents, they are studying for that time when such knowledge will become dynamite in their hands.”

To keep with the demand and times, Richmond began offering courses in aeronautics, cartography, radio, nutrition, and nursing. Civil defense preparations began to consume daily life, with attempts in the city to build an air raid siren system that encouraged civilians to follow widely communicated precautions.

“With war raging, no one knew if Richmond would be attacked,” writes Walter Griggs, R’63, L’66 and G’71, in World War II: Richmond, Virginia. “Therefore, all kinds of precautions were being taken, but most of them would prove unnecessary.”

On campus, buildings were designated as air raid shelters, including Ryland Hall, the basements in the Refectory, Millhiser Gymnasium, North Court, and Jeter and Thomas halls. Papers note that air raid warnings and blackout drills happened frequently in the city, with varying degrees of compliance.

In 1942, the West End aircraft observation post moved from the corner of Three Chopt and Patterson Avenue to the top of Puryear Hall, then the chemistry building. Griggs’ history notes that students, staff, and faculty manned the post in two-hour shifts, rain or shine. As more men left for the warfront, Westhampton students stood atop of Puryear to spot and identify aircraft.

The contributions of Westhampton’s students cannot be overstated. As the war raged on, enrollment of women increased and so did the rate at which society looked to them to fill roles traditionally performed by men. Some joined the effort overseas with the Red Cross or the auxiliary corps of the armed service branches.

“Not only is it no longer fashionable, but it’s not even patriotic, in these days to be helplessly feminized,” said Fanny Crenshaw, director of physical education. “Women have their part to do in the winning of the war, and they can’t work strenuously for long hours at difficult tasks unless they are physically fit.”

It didn’t take long for that mindset to take hold. The new Westhampton College War Council directed civilian efforts on campus. Among them were drives to sell war stamps and bonds, rolling bandages for the Red Cross, learning first-aid, and staffing the University’s aircraft warning post.

One Richmond News Leader article touted the success of women trained to identify planes. They also collected scrap metal to send to factories making war materials.

Westhampton College also began its own victory garden in the spring of 1943. They haggled with President Boatwright over how big the plot would be. Seeking a whole acre, they settled for a half-acre after the president’s counteroffer of a quarter acre near River Road. The garden would grow potatoes, tomatoes, carrots, corn, and turnips for use on campus.

“Blisters and callouses will be badges of honor in these war days,” said Martha Lucas, dean of students for Westhampton. Lucas estimated the “farmerettes” put in around 200 hours of work per week to grow vegetables, with Boatwright himself drawing upon his experience farming in Powhatan County to advise the students on the when, where, and why of potato planting.

The war affected everyone — whether in the armed services or on the home front. “Everything was rationed — clothes, food, and shoes,” says Magee, a Navy recruit. “We say we’re at war now, but this isn’t anything like what the war was for the civilian population.”

Griggs’ history notes that recipes for sweet potato coffee ran in the local paper, authorities banned driving for pleasure, and people sent spare tires back to the factories. Even alarm clocks were hard to find. Professors began biking to campus to save rubber for military vehicles.

Yet, as the war wore on, students became more scarce. There was a real concern with enrollment management.

In June 1942, the draft age was lowered to 18, and President Boatwright wrote to alumni about the steep decline in the number of men attending colleges nationwide. Dean Raymond Pinchbeck of Richmond College predicted a worrisome 20 percent decline in students for Richmond College during the 1942–43 academic year.

“Such a drop in enrollment taken with the steady decline in rates of interest on all endowments would seriously affect our ability to maintain the University,” Boatwright wrote in an appeal to alumni to recommend Richmond to students.

Pinchbeck himself would leave his post to serve as a supply pricing agent during the war, but he also wrote to his male charges that the Selective Service program called men into war as needed but, in the meantime, anticipated them continuing their studies.

“After a careful study of the present situation, and the needs of our country, it is my opinion that the very best possible service a student in Richmond College can now render his country is to do well his work as a student until the call for his active participation in the armed services is made official by our government,” wrote Pinchbeck.

ENTER THE V-12 PROGRAM

Just as the needs of the war threatened the University, they would also help Richmond endure it through a Navy training program called V-12. In July 1943, the first V-12 class took over Thomas and Jeter halls, bringing much-needed students. Richmond College professors would help train more than 800 officer candidates from July 1943 until the program closed in the fall of 1945. Among the men who came through Richmond, one went on to lead Boeing and manage the development of the 747, still considered the queen of the skies.

“I think V-12 saved the UR from closing up,” says Bill Magee, who arrived in August 1943 as part of the program. “They didn’t have enough civilian students to keep it going.”

Magee, who retired as captain after a career in the Navy, remembers hearing the news of Pearl Harbor in high school. Like many, Magee opted not to finish in order to enlist

in the effort.

“The entire country was mobilizing,” Magee says. “Everybody was going in the service — all my friends.”

Magee reported to UR for a 16-month training stint before shipping out to a salvage vessel in the western Pacific.

“We wore uniforms and observed military courtesies, which most of us knew nothing about,” Magee recalls. “The principle focus was to give us some basic academic background in order to qualify as officers.”

Richmond was one of 131 universities involved in the U.S. Navy’s largest officer training effort, which trained more than 125,000 men nationwide. Our University kept its V-12s mostly separate from civilian students. They were on a different schedule, attended their own classes taught by the Richmond College faculty, and answered to their commandant, Lieutenant J.H. Neville. Though sequestered academically, they contributed inestimably to the campus culture.

Athletics probably benefitted the most obviously. The 1943 football team — bolstered by a substantial number of former William & Mary and Washington & Lee students — lost only once that year, to Duke University, and finished as state champs. The men’s basketball team also had a great season, winning the “Big Six” title. Those victories helped bring the two student bodies together, according to James Schneider, author of The Navy’s V-12 Program: Leadership for a Lifetime.

The contributions of naval trainees spilled over into other aspects of campus life. Their band played for dances, and the campus canteen became a place for the recruits and civilian students to socialize. In 1944, the midwinter dance at Westhampton was postponed because the V-12 unit had been quarantined for three weeks after around 40 trainees contracted the mumps. Wartime volumes of The Web reveal that many clubs, faced with a shortage of men, recruited from the Navy trainees.

An Oct. 20, 1944, Collegian editorial gave full credit to the V-12s for the continued success of many activities around campus: “It was from this class of men that sprung most of our college Spirit. … Many of the organizations would now be inactive had it not been for the spirit of the members of the V-12 Unit. At first the presence of the men in Navy blue was resented, but now firm bonds of comradeship and fellowship exist.”

AFTER THE WAR

Once hostilities ended, Richmond, like many other institutions of higher education, enjoyed a boom in enrollment as young veterans returned to college on the G.I. Bill. During the spring of 1946, the campus honored its dead with a memorial service, and Boatwright awarded honorary degrees to Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower and Admiral Chester Nimitz.

The next fall, in Dr. Modlin’s first year as president, the University enrolled 3,400 students — 70 percent more than five years earlier. Of those new students, 2,000 were veterans of the war.

Paul Brockwell Jr. is section editor for University of Richmond Magazine. His fascination with World War II goes back to a first-year seminar he took on the war's portrayal in literature and film. Also, Kilroy was here.

Ernest Dervishian’s Medal of Honor citation reads like the plot of a Hollywood film. He single-handedly forced an extraordinary number of Germans to surrender while fighting and advancing around Cisterna, Italy. Despite winning the country’s highest military decoration, Dervishian, a 1938 law grad, remained humble about the work of himself and his unit that day. “God’s hand had been on my shoulder — I was lucky. My thoughts and your thoughts go out to those who have been killed, those have been wounded, those who are missing, those who are prisoners of war,” Dervishian later said at Richmond. “They are all due equal credit, if credit is to be bestowed for doing one’s duty. Countless others performed acts equal to mine. They were not so lucky.”

Ernest Dervishian’s Medal of Honor citation reads like the plot of a Hollywood film. He single-handedly forced an extraordinary number of Germans to surrender while fighting and advancing around Cisterna, Italy. Despite winning the country’s highest military decoration, Dervishian, a 1938 law grad, remained humble about the work of himself and his unit that day. “God’s hand had been on my shoulder — I was lucky. My thoughts and your thoughts go out to those who have been killed, those have been wounded, those who are missing, those who are prisoners of war,” Dervishian later said at Richmond. “They are all due equal credit, if credit is to be bestowed for doing one’s duty. Countless others performed acts equal to mine. They were not so lucky.”