Few figures were more central to the national civil rights movement of the early 1960s than the Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker, who recently donated his papers and other artifacts to the University of Richmond for study by scholars, students, and the general public.

A Virginia Union University graduate, Walker began his lifelong advocacy in Petersburg, Virginia, just south of Richmond, where he was pastor at historic Gillfield Baptist Church. Through his leadership positions in several organizations, he “orchestrated much of the civil rights movement, especially the sit-in demonstrations, that occurred in Petersburg during the 1950s and 1960s,” according to a law review article by Richmond professor Carl Tobias.

From 1960 to 1964, Walker served as chief of staff to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the civil rights organization headed by King. Walker was a key adviser on structure and strategy, helping develop, for example, the SCLC’s watershed 1963 campaign in Birmingham, Alabama. King called him “one of the keenest minds of the nonviolent revolution.”

Walker continued his religious and civil rights leadership after he left the SCLC in 1964. He became pastor of Canaan Baptist Church in Harlem, New York, in 1967 and served as an adviser on urban affairs to Nelson Rockefeller in the 1970s. He retired from Canaan in 2004.

As part of the process of creating the Dr. and Mrs. Wyatt Tee Walker Collection at the University of Richmond, Walker and his wife, Theresa, sat for an oral history interview, which was conducted by Joseph Evans, dean and professor of preaching at the Morehouse School of Religion. The following are edited and condensed excerpts from that interview.

On Wyatt Tee Walker’s Father, John Walker:

Wyatt Tee Walker: He was a brave man. He had a great influence on my life, and I appreciated him more after his death than I did when he was alive. He read Greek and Hebrew every day. He was a very scholarly gentleman and in my judgment a great preacher in the tradition of African-American preachers.

My decision to go into ministry was influenced by his appearance at Virginia Union the week before graduation. And I remember his subject, “the measure of our responsibility,” and that he took his text from somewhere in Isaiah. That’s when I decided I would go into ministry because I saw it as the most attractive means to get rid of the segregation that I had met head on in Richmond.

On His Arrest At Petersburg Public Library:

I went in the white [only] door and asked for Volume 1 of Douglas Freeman’s biography of Robert E. Lee. He was famous for his two-volume biography of Robert E. Lee, and I was kind of rubbing it in their face a little bit. They were flustered. Flustered. And somebody’s voice, I heard her say, “Call the police.”

They came, and Chief [Willard E.] Traylor said to me did I want to be bailed out? Did we have somebody ready to bail us out? So [I said], “No, I want you to do whatever you do to people you arrest.” And I think they were shocked that R.G. Williams and myself and a few others were not going to post bail. We were going to stay in jail.

I did not know that Douglas Southall Freeman was a history professor at the University of Richmond. My penchant was against Robert E. Lee more than Douglas Southall Freeman, though I knew he was a segregationist. But I always felt Robert E. Lee was guilty of treason against the United States and should not be honored as a Confederate general.

On Meeting Martin Luther King Jr.:

We first met in 1952. Virginia Union was our host for what was called then the Inter-Seminary Movement, which was an organization developed to let seminarians get together without being arrested and put in jail.

You know, it was a time of very strict segregation, and it didn’t matter to the Southern politicians that we were seminary students. King was the president of his student body at Crozer [Theological Seminary], and I happened to be the president of our student body at Virginia Union, in the Graduate School of Theology.

So he was a delegate, and I was the host. That’s how we met. And we had similar backgrounds. His father was a minister, a pastor, like my father, and we grew up in parsonages and were greatly influenced by the church life of African-Americans.

On the Birmingham Protests:

Birmingham awakened the nation to what segregation and discrimination was all about and the danger that African-Americans faced in resisting it.

From the very beginning, we knew that the key to making the change was the right to vote because we were shut out of the political system. And we had to vote for it ourselves. We couldn’t depend on the people in the nation to do it.

A year ahead of time, Dr. King gave me the assignment to go to Birmingham and plan it out. And that ended up becoming Project C, which is identified in Taylor Branch’s book about the King era. I knew that two things would move Birmingham: Mess with the money, and make it inconvenient for the white community. That was the way to make change come. I was convinced of that.

We consciously aimed at being covered on the evening news, and that was a part of the genius of our movement at that time. We did it by calculating by what time we had to have a demonstration so it could make the evening news.

On the 1963 ‘Letter From A Birmingham Jail’:

The “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” was prompted by local clergymen, a rabbi, and a black minister who said that this was not the time for protest action. Dr. King reacted to it. He was in jail, and his lawyers brought out his comments on the edge of newspapers and toilet paper and whatever paper they could provide him with.

I was the only one in Birmingham who could understand and translate Dr. King’s chicken-scratch writing. So I translated it. The Quakers, or Friends Committee, wanted to call it “Tears of Love,” and I told them no. It needed to be called what it was, a letter from a Birmingham jail.

My personal secretary, Willie Pearl Mackey, sat on a typewriter while I translated it, and she typed it. And I remember one night, about 12:30, 1 o’clock, she just is exhausted; she went to sleep on the typewriter, and I moved her over to a chair, and I continued and finished. Because I could type, I finished doing the translation. And then we had to send it back to Dr. King to make sure he was satisfied with it. So it was sent back and forth with his lawyers. So that’s the story of the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” which I think is the most important document of the 20th century.

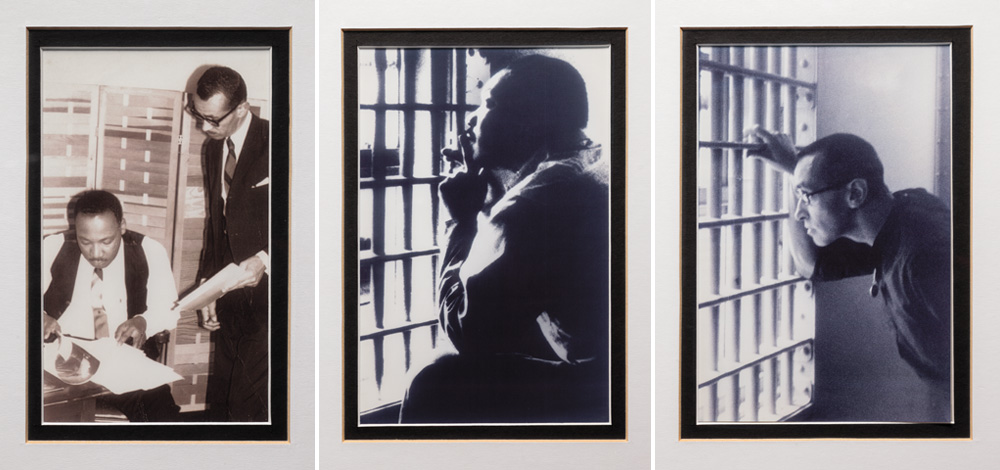

On His Widely Reproduced Birmingham Jail Photo:

Well, the picture, oddly enough, was 1967, when we went to Birmingham to give ourselves up [after appeals of contempt convictions related to the 1963 jailing failed]. Dr. King felt very strongly that if you have exhausted all of your remedies, and you have not gotten a solution, then to be faithful to the nonviolent regimen, you ought to go to jail. And he called me in New York and asked me could I meet him and Ralph [Abernathy] in Atlanta, and we would go to Birmingham and give ourselves up to the authorities, which we did. And I took that picture in that jailing. It was the only time I was in jail with Dr. King, October 1967, I think. And I took the picture of him, and then he took a picture of me. As far as I know, it was the only photograph Martin King ever took of anybody. I am very proud of that.

On Surviving A Bombing And Police Violence:

[Editor’s note: Amid the unrest in Birmingham in 1963, someone bombed the Gaston Motel, where King and other civil rights leaders were staying.]

Theresa Walker: It was Mother’s Day weekend. Ralph Abernathy and Dr. King had churches, and Mother’s Day was a big event, so they had to go back to Atlanta to their churches.

Wyatt: Dr. King wanted somebody of top administration to stay in Birmingham. He assigned me. I told him, well, I hadn’t been home in months. He told me that SCLC would fly my wife and children over to Birmingham to be with me, and that was satisfactory. And that’s what set up the situation where two of the children were in the Gaston Motel when it was bombed, and my wife was struck by an Alabama state trooper with a carbine and had to go to the hospital. After she got out of the hospital the next day and flew back to Atlanta, she was arrested in East Point, Georgia, with the four children. I’ll let her tell you about that.

Theresa: The hotel had rooms around a courtyard, and we were in one of the rooms. The lobby was at one end of the courtyard, and my two youngest children were asleep in the hotel room. Some of us were sitting outside making small talk. When the troopers came, they said everybody had to go into the lobby. I said, “I have two small children fast asleep.” The fellow just took his gun and hit me in the head.

Wyatt: I went for him. A stringer from UPI [United Press International, a news wire service], I think, from Mississippi, grabbed me and pinned me to the floor. I think he saved my life because I’m sure that a trooper would have shot me. I wasn’t even thinking about that. All I knew was that he had hit my wife — and with his gun.

On Parenting While Being Activists:

Theresa: Our children were called “children of the movement.” People didn’t understand — well, I guess their playmates and their parents, when we moved to Atlanta, even in Petersburg — they said our children talked funny and that their father was always in jail. Kids didn’t understand it then. Some of the parents could — it was just getting started good — but some of the parents didn’t understand it.

Our kids in Petersburg couldn’t go out and play unless someone was with them. Threatening calls would come over the phone, and sometimes they would answer. They paid a big price. My daughter was barred from all public schools because of my husband’s work in Petersburg. She had to be homeschooled. It was hard on children, too — and they were children, and they should have been able to have a child’s life. They did not have that. King’s children didn’t have that, nor did Abernathy’s children. So it was hard on the children. Some of our friends didn’t bother with us because my husband was always in jail, and back then, it wasn’t popular to go to jail.

On Threats:

Well, this was my country, and I loved my country, and I wanted it to be the best that it could be for my children to grow up in. And I was determined that I was going to help make it the best it could be. That was my role. And that’s what I wanted to do.

Wyatt: I couldn’t have made it without my wife. … I knew I could die at any time, so I never thought about it. I just did what had to be done at the moment.

Walker’s papers include documents from his time as King’s chief of staff and his later writings and sermons.

Detail: A book contract bearing Martin Luther King Jr.’s signature and a photograph of King relaxing while reading a newspaper.

On King’s Death:

Dr. King installed me as a minister at Canaan [Baptist Church] on March 24, 1968, and [11] days later, he was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. That was the last place he preached in New York before he was killed. I lost my preaching for six months. I just didn’t have it. I grieved so much, and walking up and down 125th Street, the stores were playing his speeches, and I could hear his voice all the time. It was the worst time of my life.

I was in the pulpit on a Sunday morning, and I got a call from [New York City mayor] John Lindsay. He said he had just talked to Mrs. King, and he asked what could he do. She said, “If you could reach Wyatt Tee Walker and tell him I’d like him to organize the funeral and the homegoing service,” she would appreciate it. So that’s how I got involved.

That afternoon, I caught a plane to Atlanta to start working on arranging the funeral. I felt it should be a state funeral, under the circumstances. [Gov. Nelson] Rockefeller supplied my transportation and gave me a staff member to go with me and do what had to be done and take over his rooms at an Atlanta motel. I went 20 or 30 miles around Atlanta and got every pair of striped trousers that I could find so that we would wear black coats and striped trousers and make it a state funeral.

We arranged for 100,000 people to come, and about 400,000 came. I measured the streets to see how many people could walk abreast of each other and timed how long it would take to walk from Ebenezer [Baptist Church] to Morehouse College. That part was in my mind, that we should march over there because marching was such a key ingredient of our protest tactics. I feel like it was one of the capstones of my organizational career.

On Not Yet Writing A Book About King:

I think part of it was the awe that I maintained for Dr. King, that I didn’t feel I was ready. I still think I need to write about him sometime because I was very close to him, and I had many, many, many conversations with him.

But I had another book I worked on called Adam, Rocky, and Martin. I worked professionally for Adam Powell, Nelson Rockefeller, and Martin Luther King Jr. I thought that would be an interesting study for me to talk about these three high-profile Americans and their strengths and their weaknesses. I remember Adam Powell; I always felt he was a very insecure man, one of the most insecure men I have ever met. I humorously said Nelson Rockefeller’s weakness was that he was white, and he was influenced by what I called his “Eurocentric chauvinism.” But for a public figure, he was the first politician I met who really understood what black people were going through, and that’s why I worked for him. He gave the money for the water system in Resurrection City [a protest site in Washington, D.C., in 1968] during the Poor People’s Campaign, and he gave us several thousands of dollars for bail money down in Albany, Georgia. He was a very unique political figure.

On The Poor People’s Campaign:

After Dr. King’s death, I became a volunteer to Ralph Abernathy, and I traveled with him organizing — or trying to organize the Poor People’s Campaign.

We did all of the things we should have done. We met with congressmen and senators and the heads of different parts of the federal government, but they just didn’t respond to our pleas and our needs. So I always felt the nation failed rather than we failed. The Poor People’s Campaign was a success in my judgment because it put poor people on the agenda of the nation. And we were just ignored.

On His Role In History:

I was just a participant in what I think was the unfinished revolution of 1776. I feel a sense of fulfillment that I had a key role in desegregating America.