Notebook

We weren’t invisible anymore

Fifty years ago, the first generation of Black undergraduate students at Richmond formed a student organization called SOBA and organized UR’s first Black History Week. Their goal was to build community and create a greater sense of belonging for themselves and the students who came after. The university will celebrate this milestone at the Black Excellence Gala in February.

Stanley Davis, R’74, remembers looking around the University of Richmond campus on his first visit and not seeing any other Black students like himself at first.

The Davis family, including his parents and two sisters, had piled into the car and driven from Hampton to Richmond. They knew how to get to the city, but they needed a map to find the university that sunny Sunday in August 1970.

His faculty adviser, history professor Barry Westin, met them in a parking lot, took them on a campus tour, and showed Davis his dorm room. While they were on campus, they met another Black freshman, Carlton Mack, R’74, and his family. They looked around. They asked questions. “My mother asked Dr. Westin, ‘How many Blacks are on campus?’” Davis said. “And Dr. Westin said, ‘Twenty-five.’”

Slightly reassured but still apprehensive about their son moving to a predominantly white campus, Davis’ parents walked back to their car with him and his sisters. “My mom looked at me and said, ‘If you want to come home, let us know, and we’ll come get you,’” he says. “No, I will be OK,” he responded.

In hindsight, Davis realized that the more specific question his mother should have asked was how many Black students were on campus. The answer at the time: 11. Westin’s higher tally included workers like janitors, housekeepers, groundskeepers, and food service employees who left at 5 p.m.

This reality would become a catalyst. By early 1973, Davis and his classmates formed the Student Organization for Black Awareness, or SOBA (pronounced so-bah). They also sponsored the first Black History Week at the university in 1974, two years before President Gerald Ford issued a message observing Black History Month for the first time. Their mission was twofold: to ensure that the university community recognized the Black students’ presence and to be included in the full university experience.

At UR, SOBA was part of a historic civil rights movement on college campuses across the country. Their leadership laid important groundwork for today’s efforts on campus to cultivate inclusive communities, empower students to be affirmed in their identities, and ensure that every Spider is part of creating the university’s future.

A Collective Decision

In addition to Mack, Davis met Black Richmond College freshmen Norman Williams, R’74, Weldon Edwards, R’75, and Sam Burleigh, R’76, in his earliest days on campus. They became close friends right away. Later he met the two Black women starting at Westhampton College, Irene Ebhomielen Sagay, W’74, and a student who later transferred.

“One thing I had going for me differently than any of the other students was that there were nine freshmen who were in high school with me,” Davis says. “So I did have people I could reach out to and talk to. That was a good thing, but as far as Black students, that was it.”

Williams, a record-smashing track star and the first Black athlete to receive a full UR scholarship, also felt unprepared for the campus environment. He spent most weekends at track meets, sometimes traveling out of state with the team by bus through areas with overtly racist signage. During the week, he hit the books, a familiar student-athlete rhythm. But the isolation wore on him.

“At first, I didn’t call it home,” Williams says. “I didn’t want to stay.”

“We were welcome … but not welcome,” Davis says. “There was no social life for us on campus. The majority of us, we would go off campus to VCU or down to Virginia State University in Petersburg or across town to Virginia Union University to see friends.”

Halfway through their first semester, the friends talked seriously about leaving. “It was everything,” Davis says. “It was the lack of a social life, the lack of being, we felt, included in the full Richmond experience.”

Instead, the young men made a collective decision to stay. All five of them went on to graduate. “Let’s make this work as best we can,” Davis says about their resolve.

By sophomore year, they discussed organizing.

“Everybody has a need to see somebody who reflects who they are. When you see people who look like you, it communicates, ‘Yes, I see you. Yes, you matter.’”

Davis, naturally outgoing, took the lead. He told Westin, his adviser, their idea about an organization for Black student awareness that could mentor students and work collaboratively with other university organizations. Westin liked the idea, but the group needed a faculty sponsor to become official.

As a double major in sociology and political science, Davis approached sociology department chair Jim Sartain, who agreed to be their sponsor. Davis and his fellow founders filed the paperwork, the university provided $500 in funding, and SOBA was born. They met Mondays at 7:30 p.m.

Their challenges were significant. Archival articles and documents show how SOBA members had to keep proving themselves, restating their purpose, offering reassurance. An ostensibly sympathetic op-ed in the Collegian in January 1974 illustrates their dilemma: “It should be made clear that SOBA is not a separatist group,” it reads. “Quite the opposite.”

When Victoria Charles, ’16, dug through SOBA’s history decades later for a post-baccalaureate project, she wrote, “They adopted the language of assimilation in order to carve out a space for themselves on the university landscape that they palpably felt did not exist.”

Shades of Unseen Beauty

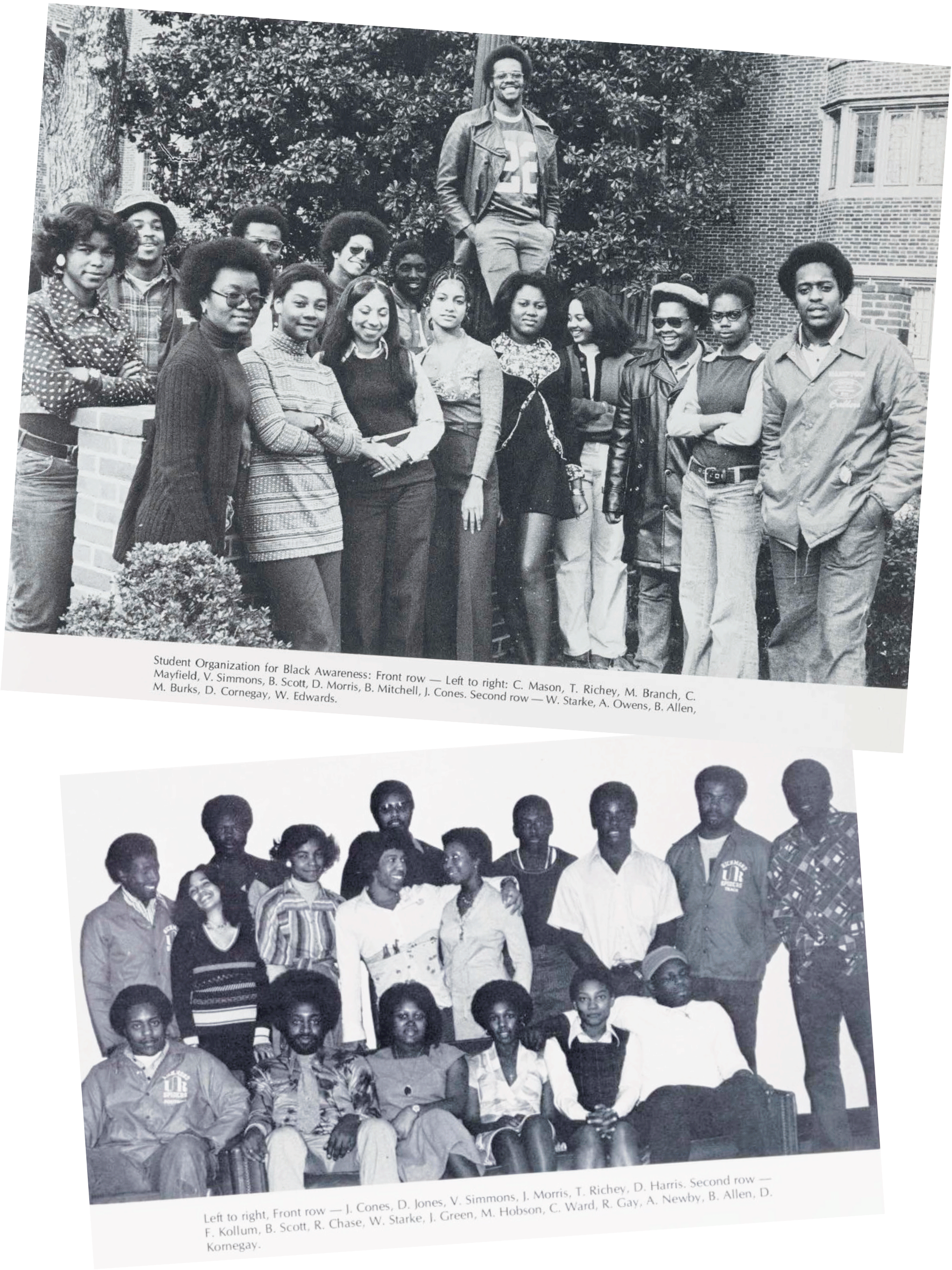

A group photo in the 1974 yearbook captioned “Organization for Black Awareness” shows 16 members but does not name them. Davis can identify everyone, including vice president “Ace” Owens, R’76, cut off on the right, historian Virgie Simmons, and secretary Wanda Starke, W’76.

Davis lists nearly a dozen other members — treasurer Williams among them — not shown because they had other school commitments or lived off campus.

Starke recalls the thought process for SOBA’s formation. “Everybody has a need to see somebody who reflects who they are,” Starke says. “And when you don’t see that in a space that you’re navigating every day, it’s hard. It’s hard because the message is communicated that you don’t matter. And then, when you see people who look like you, it communicates, ‘Yes, I see you. Yes, you matter.’”

Virgie Simmons and Rose Jackson came up with the idea for celebrating Black History Week at UR, Davis says. Aptly, the theme for Feb. 3–10, 1974, was “shades of unseen beauty.” Jackson led SOBA’s committee dedicated to the week, but pulling off everything they planned required a team effort and almost their entire budget.

Events and activities spanned a Sunday sermon at Cannon Memorial Chapel, gospel night, talent night, a performance by the VCU Players, and guest speaker Senora B. Lawson, Virginia NAACP vice president. A Saturday night dance in Millhiser Gym featured the Virginia State College band Trussel. Charles W. Howard, president of the NAACP’s Richmond branch and Black Higher Education Coalition chairman, gave remarks ahead of a rap session that drew around 50 people.

“The biggest thing for me was the rap session, where we had all the students come together, and we did have faculty members there, to express our concerns from dormitory life to academics,” Davis says. “The faculty and a couple of administrators started to understand what it was like to be on the Richmond campus as a Black student.”

Turnout for the week was lower than they hoped, and few white students participated in the events, Davis says, but SOBA did raise awareness.

“We weren’t invisible anymore,” he continues. “Now everyone knew there were students on campus of color who wanted to be included in university life and who were willing to share experiences and to work together and learn together.”

We Belong

Starke, inspired by feature articles in Norfolk’s Black weekly paper, knew in fifth grade that she wanted to be a reporter. She decided to major in journalism at Westhampton College and became the first Black student on the Collegian staff.

“I can honestly say I never had a bad moment in terms of someone saying something nasty to me or doing something unfair to me,” she says about her undergraduate days. “My relationships with people in my class, my professors, everyone on the Collegian staff — they were wonderful.”

Pain came from elsewhere. Having played the flute since elementary school, Starke joined the marching band. “This was a university that, during football games — every football game, every touchdown — celebrated with the band playing ‘Dixie,’” she says. “I remember vividly sitting or standing holding my flute while those around me played gleefully.”

Starke also watched a student circle the stadium on horseback waving the Confederate flag whenever Richmond scored. “I know it’s [now] hard to imagine that at the University of Richmond, but that was my reality for three of the four years,” she says.

Then there was the time a campus police officer stopped Davis and refused to believe he was a student, even after checking his university ID. Williams says, “You had some people who just won’t accept you, but there were a lot of people who did.”

By his junior year, Davis saw the Black student population rise to around 30. The tight-knit SOBA family pressed on with mentorship, information-gathering about campus resources and academic organizations, communication with faculty and administrators, and event sponsorship. In modern parlance, they were working to foster a sense of belonging.

Come early 1976, Starke was SOBA president and a Collegian staffer. She invited Essence magazine editor-in-chief Marcia Ann Gillespie to speak during Black History Week. Gillespie talked about feminism, women’s rights, Black representation, activism, and her experiences as a journalist. “I was beyond excited because she was someone that I really looked up to,” Starke says.

Lasting Legacy

Several original SOBA members emphasize the positive effects UR had on their lives, despite their struggles. “I got a great education, a lifelong learning,” Davis said. “I wouldn’t trade it for the world.”

Starke went on to an award-winning career in broadcast news, notably as a longtime anchor for WXII 12 News in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. An art major, Williams embarked on a colorful mosaic of a career. He paints vivid landscapes at his home in Pennsylvania and stays in touch with Davis, his best friend. Davis received his Army commission the day he graduated in 1974. He spent 22 years in service, rising to lieutenant colonel, and then had a lengthy second career as program manager for a U.S. Army training and education program. All three are retired.

The university prepared Davis well. “The interaction with various students on campus, the faculty, and the administration taught me a lot about human behavior, how to deal with difficult circumstances, and how to resolve problems,” he says.

SOBA continued until 1978 and briefly reorganized in 1982. After that, the Minority Student Union began, becoming the Multicultural Student Union in April 1993. Nearly a decade later, the Black Student Alliance formed and remains active on campus along with Sankofa African Student Alliance and West Indian Lynk. The University of Richmond Black Alumni Network, or URBAN, also keeps the legacy alive.

Morgan Russell-Stokes is the dean of student equity and inclusion, a position created in 2022, and directs the Student Center for Equity and Inclusion, or SCEI, continuing SOBA’s early efforts to make UR feel like home for more students.

Her goal is to create opportunities and platforms that raise awareness around what equity and inclusion look like, how to practice it, and how it shows up in the UR community. Day-to-day, she supervises SCEI, which supports first-generation, limited-income, LGBTQ+, and multicultural students.

“These students in the ’70s introducing Black History Week at a time when Blackness was not celebrated … says a lot about their tenacity, their bravery, their willingness to put themselves out there.”

“These students in the ’70s introducing Black History Week at a time when Blackness was not celebrated nationally by everyone — whether you were Black or not — says a lot about their tenacity, their bravery, their willingness to put themselves out there,” she says.

Her office plans to recognize 50 years since the first Black History Week and the original SOBA members who made it happen at the Black Excellence Gala in February — what is now Black History Month. Much has changed in the last half-century, and the center’s celebratory programs are part of broader UR efforts to build a more diverse, equitable, and caring community — a main focus area in the current strategic plan.

“The University of Richmond is a very different place and I’m grateful for that,” Starke says. “I hope students feel like they belong, that there’s a space for them, that they matter.”

Davis also compares past and present. “We’re still in a state of struggle and upheaval socially,” he says. “I’m hoping that we get to the point where not only the Black students or students of color, but all students recognize the contributions that each one can give to better themselves and to better the university.”