TAKE A STROLL THROUGH THE UNIVERSITY’S MUSEUMS, and you’ll see works that are beautiful, compelling, delightful, and provocative. Increasingly, they are also something else: an ongoing record of campus intellectual life.

When Issa Lampe took the helm as executive director of the University of Richmond Museums in 2022, she brought with her an approach that emphasizes the university art collections as an essential teaching resource. “Works of art are interdisciplinary by nature and can support classroom discussions on a wide variety of topics, from economics to literature to chemistry,” Lampe says. “You should be able to look at the collection in 20 years and see reflections of what the academic community was wrestling with.”

She actively engages faculty and students in discussions about how the collection can support teaching needs. She also solicits their active participation in acquisition decisions.

A new exhibition, Look Again: Art for Our Curriculum, showcases this intersection between the collection and the curriculum. Alongside the featured works, students and faculty reflect on the pieces’ relevance to their studies.

The exhibition runs through May 17. More information about it is available at museums.richmond.edu. Here’s a sneak peek of some of the works and excerpts from faculty reflections about them.

“UNTITLED, SHADY GROVE, ALABAMA,” 1956 • GORDON PARKS

In my Journalism Across Media class, I always teach work by Gordon Parks not only because his images are technically precise and beautifully rendered but also because his work is a model for purposeful storytelling. Of his decision to become a photographer, Parks once told an interviewer, “I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs.” This idea that journalism has power that can be directed toward fairness, equity, and justice really resonates with my students.

—Andrew Grace, assistant professor of journalism

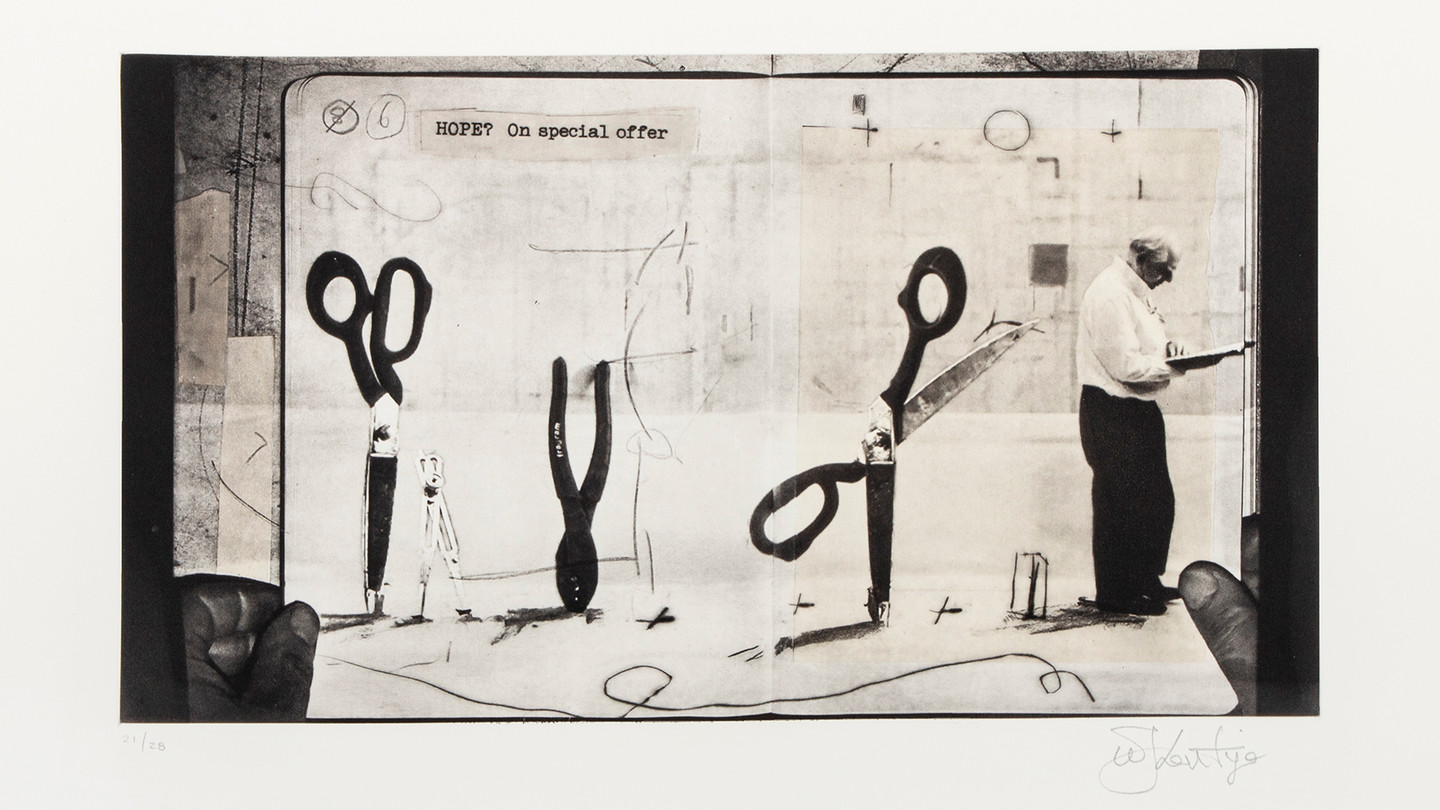

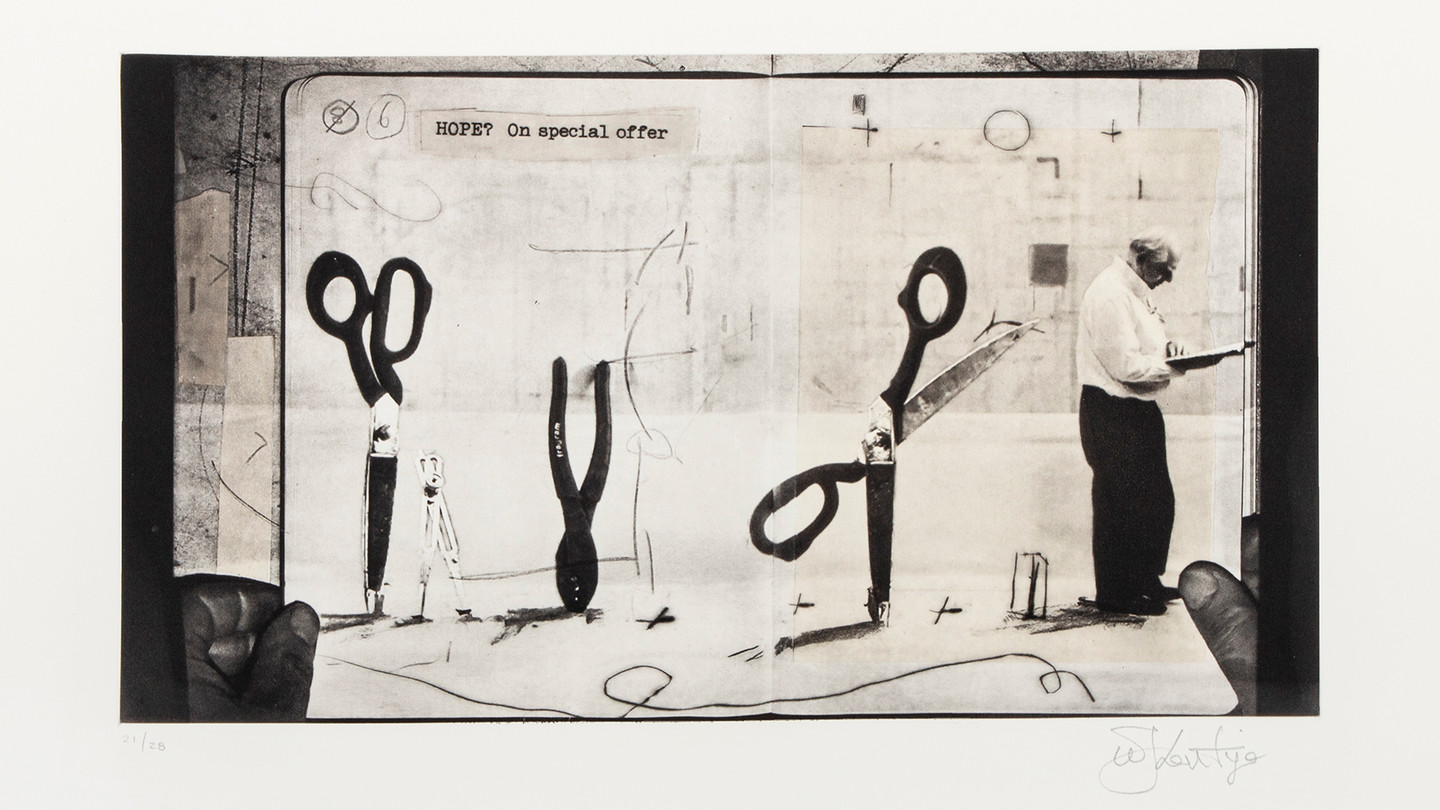

“STUDIO LIFE: HOPE? ON SPECIAL OFFER,” 2022 • WILLIAM KENTRIDGE

The image of this print oscillates between a surface and a space: We are looking into a tight frame of the photogravure that shows an artist’s hands holding an open sketchbook just above a well-used drafting table that opens up another dimension, a white stage sloping toward the bottom. A photomontage of animated tools and Kentridge himself inhabit this stage. And then, there are drypoint marks, engaging with the objects and figure or calligraphically lounging at the bottom of the image. The print is a beautiful example of Kentridge’s endless playful, creative innovation in the space between drawing and theater.

—Tanja Softić, Tucker-Boatwright professor of art and art history

“BALEISHÍSSHUUXE (BUCKSKIN PANTS),” FROM THE SERIES OUR SIDE, SET E, 2023 • WENDY RED STAR

Wendy Red Star’s Our Side, Set E series invites us to join the artist herself in reexamining how Indigenous material culture has been exhibited in settler museums. … By repositioning them in new configurations and incorporating handwritten captions, along with the images of the artist/curator’s hand into the artwork, Red Star reclaims Indigenous agency in curating Indigenous material culture and art. … [In this work], her handwritten notes supply the names of the Apsáalooke people who owned such objects, along with the names of their relatives, thus extending their histories into the past, beyond acquisition by private collectors and public institutions.

—Monika Siebert, associate professor of english

“ONE BRONZE TOOL,”

“ONE STRIP OF HIDE WITH FUR,”

“ONE CARVED WOODEN (WEAVING?) TOOL,”

“ONE DARK-COLORED FLINT PIECE WITH POST-IT,”

“TWO COWRIE SHELLS IN BAG WITH POST-IT,”

“ONE FLINT STONE TOOL,”

2016 • GALA PORRAS-KIM

When I first encountered the work of Gala Porras-Kim, I found myself immersed, literally physically surrounded, by her research in a reconstructed office from which an archaeological dig and exchange were documented for further investigation, like a crime scene. … What I love about Porras-Kim’s work, aside from its beautiful and meticulous attention to materiality, is the way in which art history’s and archaeology’s historical methods and intentions are called into question. Thinking about these works and Porras-Kim’s conceptual project is the perfect way to begin and end my course on the history and theory of collecting.

—Elena Calvillo, associate professor of art history

“STEPS (WATER LIFE),” 2018 • AÏDA MULUNEH

This work addresses urgent issues of water security and the lack of access to clean water, which has a particularly devastating impact on the lives of women and girls. Muluneh has said, “I realized a lack of access to water affects women, not only with regard to health but also education. During menstruation, for example, girls often choose not to attend school because of the lack of proper facilities.”

In Steps (Water Life), the structure represents a toilet with a raised red door which makes access impossible. Muluneh asks, “How is it that across the world and even across Africa access to water is still a challenging issue that we have to navigate through?”

—Kimberly S. Newberry, visiting assistant professor of art history

“UNTITLED (EAST END CEMETERY),” 2019 • BRIAN PALMER

Brian Palmer is a Peabody Award-winning journalist and photographer who relocated to Richmond, Virginia, in 2013 after visiting to uncover lost information about his family history. In this photograph from a series made over several years and dedicated to a cemetery in Henrico County, he presents a verdant woodland with shoulder-high weeds and towering vines lit up by summer sunlight. The photographer’s choices—time of day, framing, angle, distance, and depth of field—produce a visual experience in which we may not see the headstone in the overgrowth at first. We discover it only after a bit of looking, much as the photographer would have done. The gravestone is carved with the words “James A. Malone / Virginia / U.S. Army / World War / [dates obscured].” Under Jim Crow segregation laws, Mr. Malone’s family would have been barred from interring their loved one in any of the well-maintained, publicly funded cemeteries where his white peers lie, just a short distance from East End Cemetery.

—Issa Lampe, executive director of University of Richmond museums

“THE DIXIE OF OUR UNION,” 2022 • BETHANY COLLINS

As I teach my students, sheet music is not music; rather, it is a set of graphic instructions for how to replicate and perform a piece of music and which we can study “outside” of musical time. Historically, music theory as a discipline largely elided questions of historical context and framing and focused solely on “the music itself.” In the theory classes I teach, I instead explicitly highlight these historical contexts and how they can inform our theoretical analyses. Collins’ “The Dixie of Our Union” similarly draws attention to sheet music as replicant (here, hand-drawn) and as historically situated.

—Stefan Greenfield-casas, visiting assistant professor in music theory

“TOGETHER, SAN VICENTE BLVD, WEST HOLLYWOOD,” 2013; “NANNIES, EL TOVAR PLACE, WEST HOLLYWOOD,” 2012; “GARDENER, NIMES ROAD, BEL AIR,” 2013 • JAY LYNN GOMEZ

Jay Lynn Gomez’s depiction of domestic and service workers during their workday brings before the audience issues such as the meaning of work and its emotional dimension. As we stand in front of these images, we can re-examine the role played by the narratives of “emotion” in the discourses that embody generalized or internalized social perceptions of domesticity and cleaning. … These images help audiences explore a central subjectivity dilemma: How do we relate to the daily tasks, such as cleaning and dealing with “dirt,” in our daily material reproduction?

—Karina Elizabeth Vázquez, director of community-based learning for latin american, latino, and iberian studies

“PUNCHED 100,” 2011 • ASPEN MAYS

A star is a luminous, glowing ball of hot gas, mostly hydrogen. They are unique celestial bodies whose twinkle comes from their individual, internal energy sources. According to NASA, astronomers estimate that the universe contains up to one septillion stars (that’s a one followed by 24 zeros). Aspen May’s “Punched 100” provides an archive of discarded, anonymous stars. Salvaged from the garbage in an abandoned observatory in Chile and uniformly captured by his holepunch, their energy here is different but still magnificent.

—A. Joan Saab, executive vice president and provost

“ARBORETUM TRIPTYCH 1,” “ARBORETUM TRIPTYCH 2,” AND “ARBORETUM TRIPTYCH 3,” 1998 • JOELLYN DUESBERRY

Duesberry’s landscapes strike me for their personalized observations of place that often extend beyond the seen, particularly invoking touch. While viewing her paintings, I’ve recalled the sensation of walking up loose and rocky eroded banks of streambeds or sitting still under the sun’s heat on brisk clear days. Like candid speech, her paintings reflect affinity for flat, neutral midday light, whether crisp and dry in New Mexico or soft and humid in Virginia. … As a monoprint, I think of pressure and how ink and color is pressed into, less onto, the silk as an inseparable whole—much as I imagine Duesberry’s desired immersion into the outdoor spaces she inhabits and paints.

—Erling Sjovold, professor of art

“SNIPER II,” FROM SMALL WARS, 1999–2002 • AN-MY LÊ

Utilizing strategies and visual cues from documentary photography, An-My Lê’s “Sniper II” plays with our notion of fact and fiction in image creation. Although the scene is from a contemporary Vietnam War reenactment staged in Virginia, Lê utilizes the standard film and formatting of photojournalism of the 1950’s–70’s to lead the viewer to accept the photograph as a truthful document of war. In addition to providing a stunning portal into how the coastal landscape of Virginia can be conflated and entangled with the foliage and fraught histories of Vietnam, this image also serves as an excellent example of how choices in film size, stock, and presentation can contribute to the concept of a body of work.

—Brittany Nelson, associate professor of photography and extended media

“COUPLE IN RACCOON COATS,” 1932 • JAMES VAN DER ZEE

James Van Der Zee was the leading portrait photographer of the Harlem Renaissance, the epicenter of African American culture in the 1920s and 1930s. As a professor of American literature and culture, I have long found this image quite useful to share with students so they can recognize the class diversity in the community of Harlem in those decades that extends beyond the stereotype of the struggling writer/artist/musician.

In this photo, Van Der Zee has captured a couple deeply comfortable in their material success, signaled not so subtly through their raccoon coats and shiny Cadillac. That this couple chose to have their portrait taken out in the open and not in Van Der Zee’s studio suggests that they wanted to emphasize these symbols of conspicuous consumption. And why not? They look fabulous!

—Stephen Brauer, visiting associate professor of English