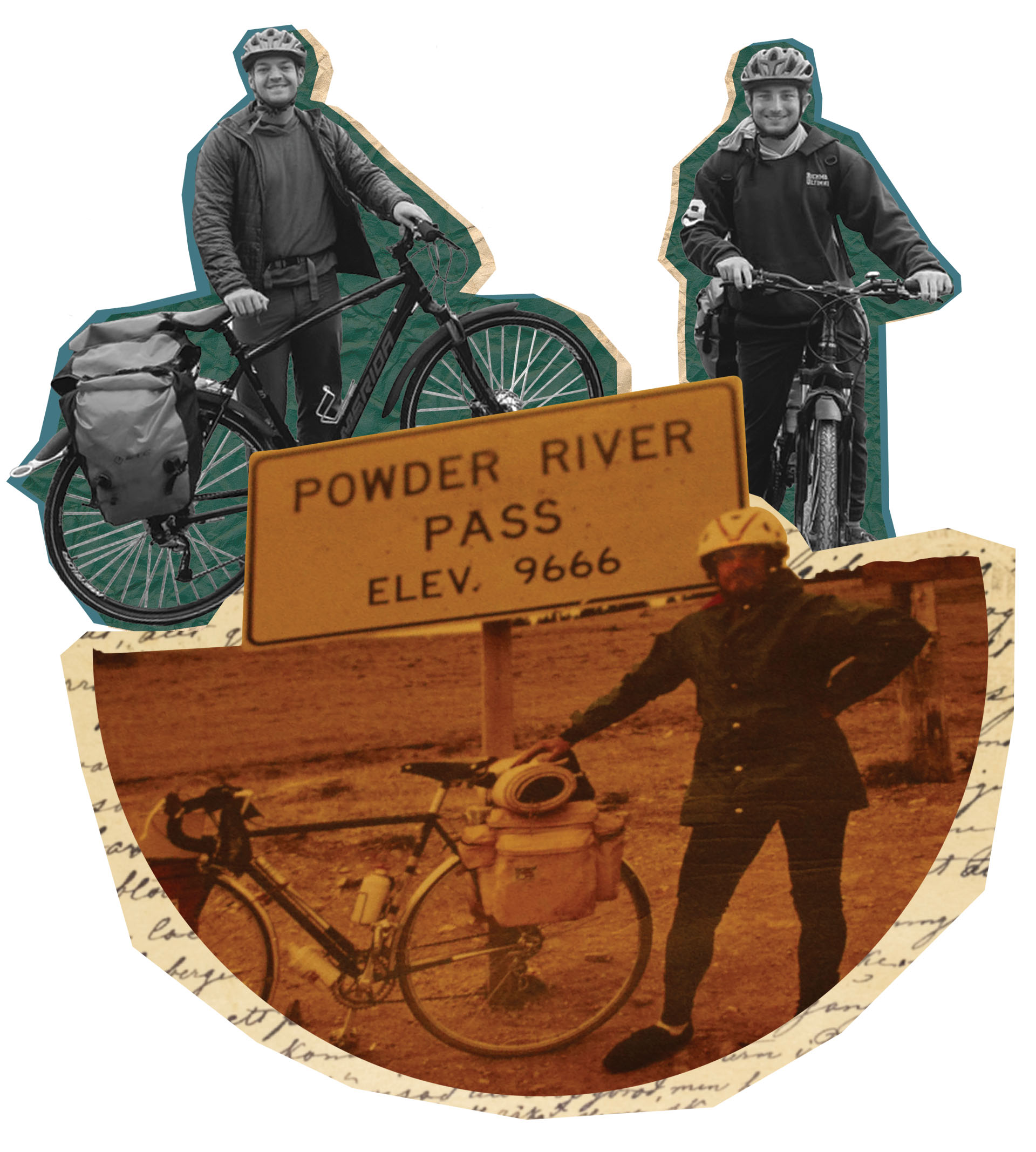

HARSH WYOMING WIND CUTS ACROSS AN EMPTY road that stretches toward the horizon. A solitary cyclist, his neon green and orange bike laden with camping gear and cameras, pedals steadily forward. Nineteen days without human connection — save for fleeting interactions with curious strangers — have left him in a peculiar mental state. His thoughts flow, a smooth river unobstructed by the distractions of modern life.

“My conscious had mastered control over my subconscious,” says Eli Beech-Brown, ’24, describing the meditative headspace he achieved during his cross-country cycling journey. “I was incredibly present.”

Several states away, his best friend Miles Goldman, ’24, anxiously checks his location on Find My Friends, worrying about Beech-Brown’s well-being in the wilderness. When they finally connect over a phone call, Goldman is bombarded with philosophical revelations.

“He would be rattling off the most insane thoughts one after another,” Goldman says, laughing. “I was like, ‘Oh God, has he descended into madness?’ He’d be saying things like, ‘My body’s a machine,’ or, ‘I’m a wild animal — I am no different than the grizzly bears out here.’”

This intense, illuminant bicycle journey across America wasn’t just a physical challenge for Beech-Brown. It was a deeply personal pilgrimage to connect with his late father, who completed a similar journey decades earlier. And a documentary film that Goldman produced about the experience wasn’t just a creative endeavor — it was a testament to a profound friendship that emerged on the University of Richmond campus.

A FRIENDSHIP IS BORN

Their story begins, appropriately enough, with bicycles.

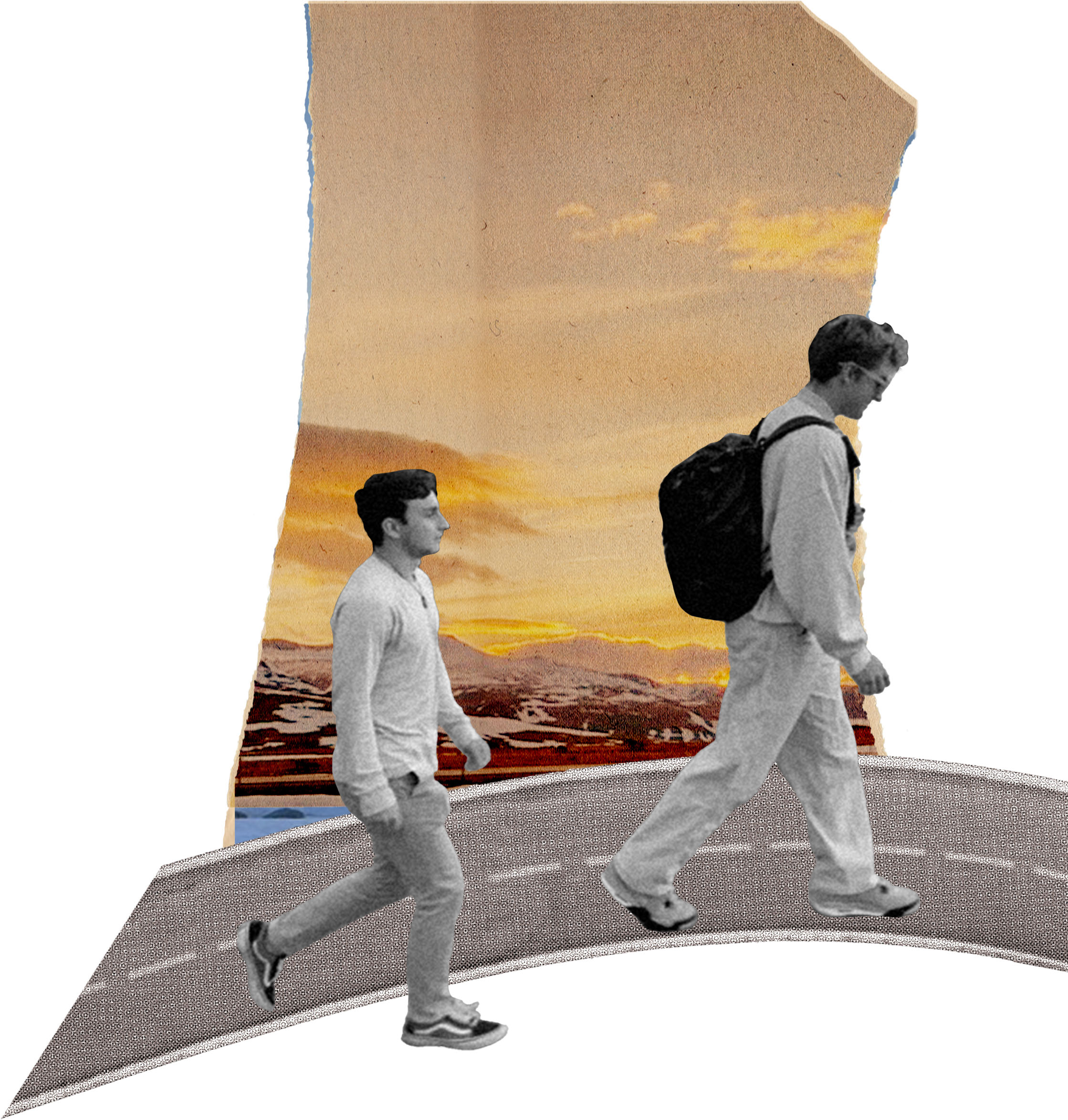

Like many friendships forged during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Beech-Brown and Goldman initially connected through one of the few social outlets available to Richmond students at the time: club sports. As first-years living in the same residence hall, they joined the Ultimate Frisbee team (affectionately known as the Spidermonkeys) and quickly discovered a mutual appreciation for cycling.

“My earliest memories of connecting with Eli on a deeper level were on bike rides we would take together outside of campus,” Goldman says. They would regularly pedal across the bridge to Pony Pasture, jump in the water, and bike back, still wet, in the darkness. “Those were always refreshing times to check in with each other and talk about the hardest things — or the most important things.”

By sophomore year, their bond had deepened considerably. It was during one particular walk across Westhampton Green that Beech-Brown first mentioned his dream of retracing his late father’s cross-country bicycle journey.

Beech-Brown’s father, Jeff, had passed away unexpectedly a few years prior. He recounted Jeff making this lengthy post-graduation ride, pedaling alone from Michigan to California. Seeking to process his grief and reconnect with his father in spirit, Beech-Brown vowed to do the same.

“The sun was setting. It was a beautiful Richmond sunset,” Goldman says. “And he tells me, ‘Hey Miles, I’m going to do this cross-country bike ride after I graduate.’ He tells me about his dad’s story doing it, about [his dad’s] journals, and that was the moment he said, ‘And you know what? I want you to come with me, and we’re making a documentary out of it.’”

At the time, it seemed like one of Beech-Brown’s many ambitious ideas that normally never materialize. Goldman admits having reservations about whether his friend would actually follow through with such a physically demanding journey. “I had serious doubts,” he confesses. “I was telling my parents, ‘Eli’s leaving. I really don’t know how long he’s going to make it.’”

“He’d be saying things like, ‘My body’s a machine,’ or, ‘I’m a wild animal — I am no different than the grizzly bears out here.’”

For Beech-Brown, this journey was far more than an athletic challenge. It was about connecting with the father he lost when he was 18.

“This was a story that was as key to me as any children’s book I had,” Beech-Brown says. “It was my childhood, a story that had been repeated to me over and over—not only about the cycling, but more so about the lessons applied through that experience and how that shaped my dad’s life.”

After his father’s death, the journey took on new significance. “It presented the opportunity for me to connect with him in a way that I don’t think I could in any other manner,” Beech-Brown says. “There’s something powerful about being in the exact same place and generating a shared experience when no other shared experience is possible.”

The relationship between Beech-Brown and his father had been complex. He learned to ride a bike at age 3 when his father pushed him down a steep parking lot on Michigan’s Madeline Island repeatedly until he got it. From then on, they rode together regularly, though Beech-Brown admits their relationship wasn’t always smooth, particularly during his teenage years.

“It had kind of descended and was rebuilding in a way that I was very happy about when he passed away,” Beech-Brown says. “I think that was one of the hardest parts about his death — we were just at a moment where things were starting to take a shape that I was hoping they would.”

This cycling journey became a way for Beech-Brown to process his grief — something he had struggled with throughout college. The bicycle, which had been a constant connection between father and son, became what Beech-Brown describes as “a Ouija board-like connection” to his dad.

A DREAM BECOMES REAL

While the concept of documenting Beech-Brown’s journey had been discussed since sophomore year, serious planning only began about a month before his departure. The pair connected with a director named Hunter Smalling, owner of Puzzleworld Studios, and suddenly the project started taking shape.

But even as Beech-Brown prepared to depart, nothing was certain. “Even when I left, we weren’t sure we were going to make a film,” Beech-Brown says. “I just brought the cameras, and we were like, ‘Well, we’ll see.’”

For Goldman, a mathematical economics major with aspirations in filmmaking, the project represented a perfect confluence of personal and professional interests. “How often does anybody get to combine their career aspirations and have their first professional project be about somebody they care about so much?” he asks.

The journey began in Duluth, Minnesota, with Beech-Brown riding solo while Goldman coordinated from afar. The original plan had been for Beech-Brown to train for two more weeks, but in a spontaneous phone call, he announced he was leaving immediately.

“I felt the most confident I’ve ever felt in my life. You’re incredibly self-sufficient.”

“He calls me and he’s like, ‘I’m fired up, bro. I’m fired up,’” Goldman recounts. “I’m like, ‘What?’ He’s like, ‘I’m just going to go. I’m ready. I feel it in my veins.’ I’m like, ‘Weren’t you going to take two more weeks to train for this? You’ve only done two practice rides.’ And he goes, ‘Nah, man, I know it’s time. I’ve got the mental edge.’”

The early weeks of Beech-Brown’s journey were emotionally complex, particularly as he grappled with extended solitude — something he had never been comfortable with.

“The first few weeks were extremely challenging,” Beech-Brown says. “I struggled a lot with sense of self. Who are you when you are completely alone, in comparison to building a sense of self through relationships with others?”

His days took on a monastic simplicity: Wake up, eat, stretch, pack, bike for eight hours, unpack, eat, stretch, read, write, sleep. Repeat. Every day for 100 days.

“All there is to do is think about who you are and every decision you’ve ever made,” he says. “It was just intense and a lot to handle.”

The experience was punctuated by occasional visits from friends, including other Spiders, though these encounters sometimes made the journey more difficult. After friends left, Beech-Brown experienced what he describes as the difference between solitude and loneliness.

“It’s one thing to spend three days alone and then another 10 and kind of become accustomed to this routine and that sense of solitude,” he explains. “But when someone comes and then leaves, there’s a sense of loneliness.”

The longest stretch without human connection came before Yellowstone — 19 days traversing Wyoming with limited internet access and only brief, superficial interactions with strangers. “It was death by a thousand cuts,” Beech-Brown says of these encounters. “You get the same question a thousand times, yet there’s no depth.”

Yet in this stark isolation, something remarkable happened. Beech-Brown found a profound mental clarity and a previously untapped strength.

“I felt the most confident I’ve ever felt in my life,” he says. “You’re incredibly self-sufficient. It’s just me, and I just have to go up this mountain, and I don’t have another choice, and there’s no one to help. And if you do that over and over for 100 days, you feel pretty damned good.”

A FRIENDSHIP SUSTAINED

Throughout the journey, Goldman remained Beech-Brown’s lifeline, receiving phone calls every few days filled with philosophical musings and raw emotion.

“I was there through the hardest times, like when he was stuck with an injury for three days in a hotel room,” Goldman says. “That was probably one of the lowest points. And just telling him, ‘You’re going to be back on the bike so soon.’”

Goldman marveled at his friend’s mental transformation, particularly during their reunion in Colorado, where they conducted what both consider the most powerful interview of the documentary.

With a stunning Rocky Mountain backdrop and a setting sun, Goldman interviewed Beech-Brown about his journey. What started as a list of prepared questions quickly evolved into the kind of deep conversation the two friends had always shared — focused on relationships, grief, and love.

“It was so beautiful,” Goldman says simply, emotion evident in his voice. “It was crazy.”

“All there is to do is think about who you are and every decision you’ve ever made. It was just intense and a lot to handle.”

For Beech-Brown, the presence of Miles throughout the journey — whether physically or through phone calls — provided a crucial anchor. “Miles provides a stable presence,” he explains. “I’m prone to being erratic, and my life changes rapidly, often. I find a great stability in Miles that gives me the confidence to continue to pursue a life that is erratic and challenging because I know that there is some sort of unconditional love that is behind me at all times.”

Goldman echoes this sentiment: “I know that I can live my days however I choose or let somebody down or do something that I may not love myself for, but at the end of the day, I always have somebody there for me. And that is the best feeling in the world.”

THE END OF A JOURNEY

Their film together came to be called Tailwind of Love. Asked how their friendship changed after the journey and documentary project, both pause thoughtfully. Their answer is somewhat surprising.

“I actually don’t think that much has changed,” Beech-Brown says. “But I think that’s really awesome. I think the trip and the film were a culmination of what we had practiced and built over four years.”

Goldman agrees. “I definitely understand Eli more now, obviously,” he says. But the most meaningful outcome is the film itself — a permanent record of their friendship. “Personally, to me, it’s a testament to our friendship ... having the film itself and having it for the rest of our lives.”

The project did introduce new dimensions to their relationship, blending friendship with professional collaboration. “There’s a dichotomy between friendship and professionalism in some ways,” Beech-Brown says. “That is challenging sometimes because, logistically, we might only have an hour, but we need to have an hour discussing film budgets instead of interpersonal relationships.”

“I didn’t want to copy his trip completely because it was also my trip, in diverging from part of his route, I was making it somewhat my own.”

Nevertheless, their friendship remains grounded in the same qualities that defined it at Richmond: deep conversation, unconditional support, and a shared capacity for introspection.

“Our relationship has always been super introspective,” Goldman says. “I think it’s largely due to his worldview and love for learning. He pushes me to think greater about myself and my place in the world and the people that I love. Every time we get on the phone, it’s like I have a new vigor for life because we talk about some big theme. ... I don’t have that relationship with anybody else.”

Both Beech-Brown and Goldman think fondly of their student days on campus, where their friendship took root, strengthening each year that passed.

“At Richmond, me and Miles really worked strongly to curate a relationship and a worldview that led us to pursue things like this,” Beech-Brown says. “I’d say a kind of veracity for life and willingness to take risks in order to feel that sense of aliveness.”

Goldman nods in agreement. “At the end of the day, Richmond brought Eli and I together, and I’ll always be grateful for that.”

Throughout their Richmond years, cycling remained a constant — from those early rides to Pony Pasture to regular trips to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. These smaller journeys foreshadowed the epic quest to come.

“I can see how [the] bike rides Eli and I went on in college [scaled up] to this massive trip,” Goldman observes. “[They’re] not only a vehicle for getting places, but for navigating your thoughts.”

A LOOK TO THE HORIZON

The documentary about Beech-Brown’s journey is still being finalized, with both friends deeply invested in crafting the final product. Goldman returned to campus in the spring to screen the latest version and receive feedback from film faculty. He is eyeing a release date sometime in 2026.

Despite now living in different countries — Beech-Brown in Chile and Goldman pursuing filmmaking in the United States — they remain committed to maintaining their bond. In fact, they managed to see each other every month for five straight months after graduation until Beech-Brown’s departure for South America.

And they’re already planning their next adventure. “One day Miles will go on a bike trip with me,” Beech-Brown insists. “On a tandem. That’s my dream.” When Goldman chuckles, Beech-Brown doubles down. “That’s not a joke. Might be next year too. Might be next summer.”

Whatever form their next adventure takes, it’s clear that the friendship forged at Richmond and strengthened through this remarkable journey will continue to be a defining force in both their lives. As Beech-Brown rode across America processing his grief, he discovered the power of love — not just the love he had for his father, but the steadfast love of friendship that carried him through the journey.