Almost 20 years ago, I saw the delightful film The Bucket List. I instinctively knew I must make such a list for myself. When my list was finished, it consisted almost entirely of faraway places that I wanted to visit. High on that list was the country known as the Hermit Kingdom, North Korea. But standing in my way were dire warnings from the U.S. State Department.

“Do not travel to North Korea due to the continuing serious risk of arrest and the threat of wrongful, long-term imprisonment,” one advisory read. “Do not travel to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea for any reason.”

Then I heard about a U.K.-based tour company that could obtain entry visas for U.S. citizens. There was a way I could visit this autocratic country that is completely isolated from the rest of the world.

I booked a five-day trip for October 2008, a decision that set in motion the most unusual, demanding, and controlled journey of my more than 150 trips outside the U.S.

“The most unusual, demanding, and controlled journey of my more than 150 trips outside the U.S.”

I had to meet specific requirements to get an entry visa. For example, all tour members had to arrive in Pyongyang via a flight on Air Koryo, the official state airline of North Korea. This requirement means that the tours must originate in Beijing, China, one of only a handful of cities in the world that allow Koryo aircraft to use its runways because of sanctions and safety concerns about the airline. My plane was a Russian-made Tu-134. This type of aircraft was manufactured in the 1960s and sold to Air Koryo decades later. I will say this: The Koryo fleet is not in the Airbus category. Koryo has been consistently and, in my experience, deservedly voted the world’s worst airline for many years.

After I booked the trip, the tour company emailed me a list of “helpful facts for tourists.” Some of them were just petty annoyances. For example, I would be unable to receive emails while in North Korea; however, I would be permitted to send an email from the hotel’s computer café provided I paid a fee and agreed to have it read before transmission. Also, I must never, ever attempt to walk outside my hotel unless in the company of a licensed tour guide.

About two weeks before leaving, I received another set of advisories. These were more serious. There was a sternly worded dictum that warned me never to say or write anything even remotely critical of North Korea’s deceased leader Kim Il Sung or any of his descendants, including the nation’s then-current leader, Kim Jong Il. Also, I must never take a photo unless I have received permission from the tour guide. There were several pages of these “words of advice” that ranged from silly and inconvenient to downright scary.

On the day before my flight from Beijing, I received yet another email informing me that I must store most of my personal belongings at my hotel in Beijing. This list included any English-language newspapers, magazines, or books (and specifically any part of the Bible) and all electronic devices such as cell phones, computers, laptops, iPads, and tablets.

The 70-minute flight to Pyongyang was uneventful, although the seating was cramped and uncomfortable. After we landed, I walked across the tarmac and entered a small arrivals hall. Our group leader produced visas and passports that North Korean border officials carefully scrutinized. Next, everyone’s luggage was opened and thoroughly inspected. The customs officials even opened my toiletries bag, removed the cap from a tiny bottle of shampoo, and gave it a sniff. A question I had been asking myself returned to my mind once again: “What are these people afraid of?”

The entire arrivals area was ringed with heavily armed security personnel. Several of these officers led muzzled German shepherds on long leashes, allowing them to roam among the incoming tourists. If the idea was to intimidate, it was working.

My group of about 30 people included about 10 whose first language was English. We were separated and put on a bus by ourselves. No reason was ever offered for this segregation; the guides on all of the buses spoke fluent English. The lack of any apparent rationale caused a twinge of paranoia to resurface.

“There were several pages of these ‘words of advice’ that ranged from silly and inconvenient to downright scary.”

Our English-speaking bus was staffed with the local guide, a driver, a trainee guide, and a “back-of-the-bus” guard. The purpose of the latter two staffers seemed to be to ensure that we did not say anything critical about North Korea or any of its leaders and to make sure we did not take any unauthorized photos along the way.

Our first stop, even before the hotel, was along the banks of a tributary of the Taedong River where the USS Pueblo is moored. It was captured by the North Koreans in 1968 and today serves as a kind of museum attesting to the power of the North Korean navy. Once onboard this vessel, I got my first glimpse into the world of the North Korean propaganda machine.

The guide on board the ship recounted what he called a “dramatic” sea battle that led to the capture of this U.S. ship. He told how 19 navy ships captured this American “destroyer,” in his words, with air support from a small squadron of Russian MIG fighter jets. Of course, the USS Pueblo was not a destroyer. It was a spy ship stripped of most of its armaments. When North Korea captured it, it was crammed full of radar, communication, and spy apparatus. A couple of North Korean gunships could easily have done the job.

The hotel in Pyongyang, situated on a tiny island in the Taedong River, was much more modern than I expected. It is available only to foreigners. As our luggage was sorted, I approached the guide and asked him how he had developed such non-accented English that was perfect down to obscure idioms. He told me he had spent two years at King’s College, London.

Mills flew from Beijing to Pyongyang on Air Koryo, North Korea’s state airline.

The tour's first stop, even before the hotel, was the USS Pueblo, an American spy ship captured by North Korea in 1968.

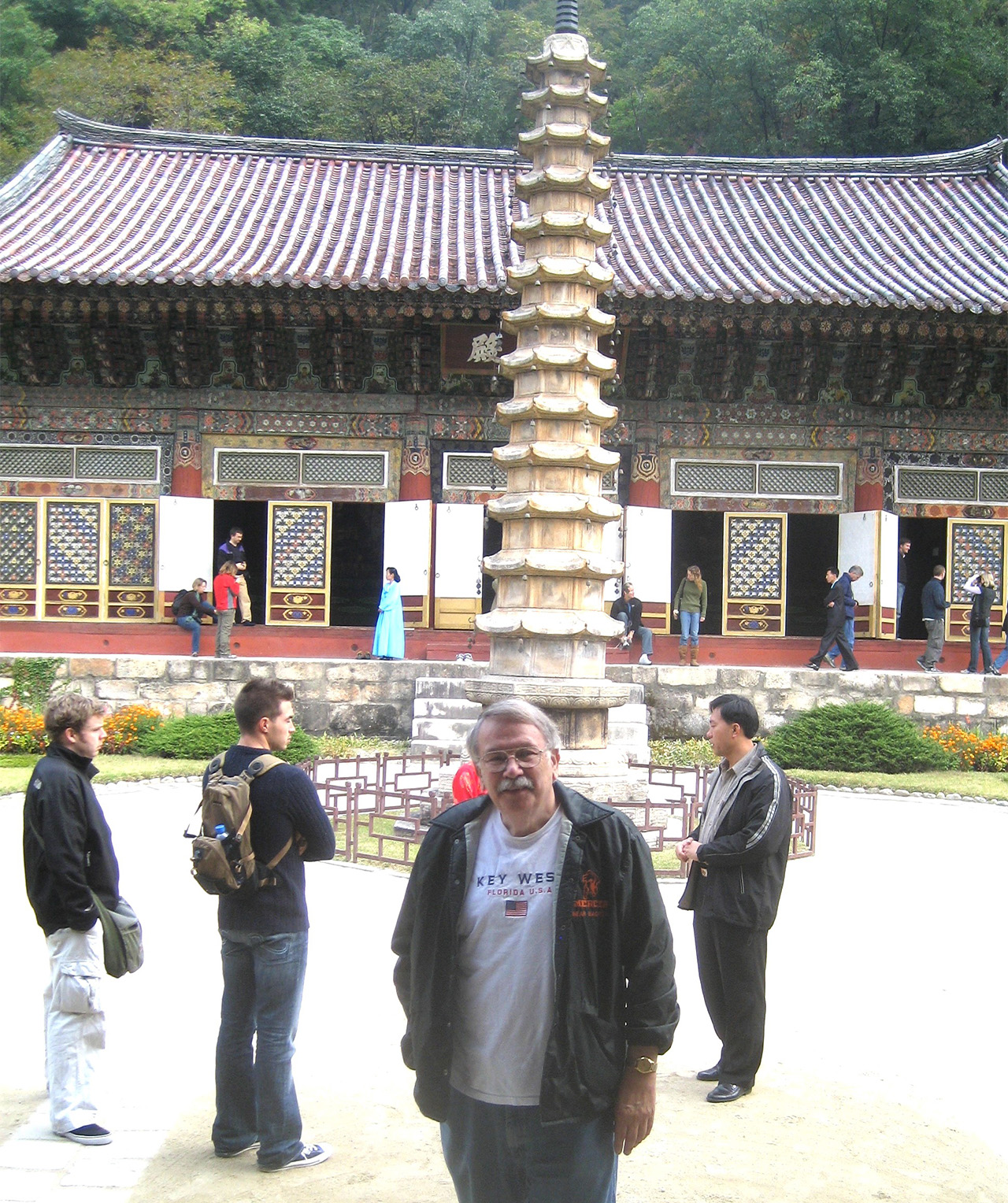

The visit included stops at sites that venerate the country’s leaders.

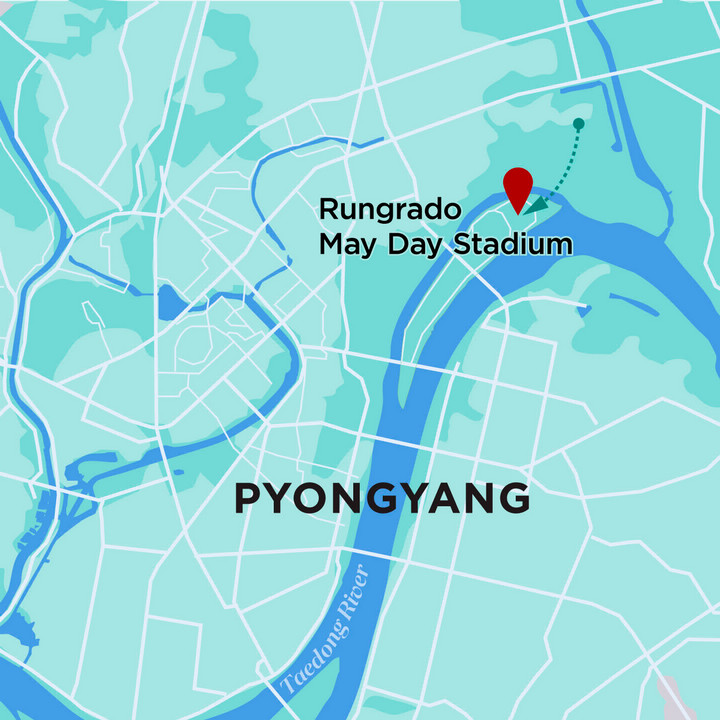

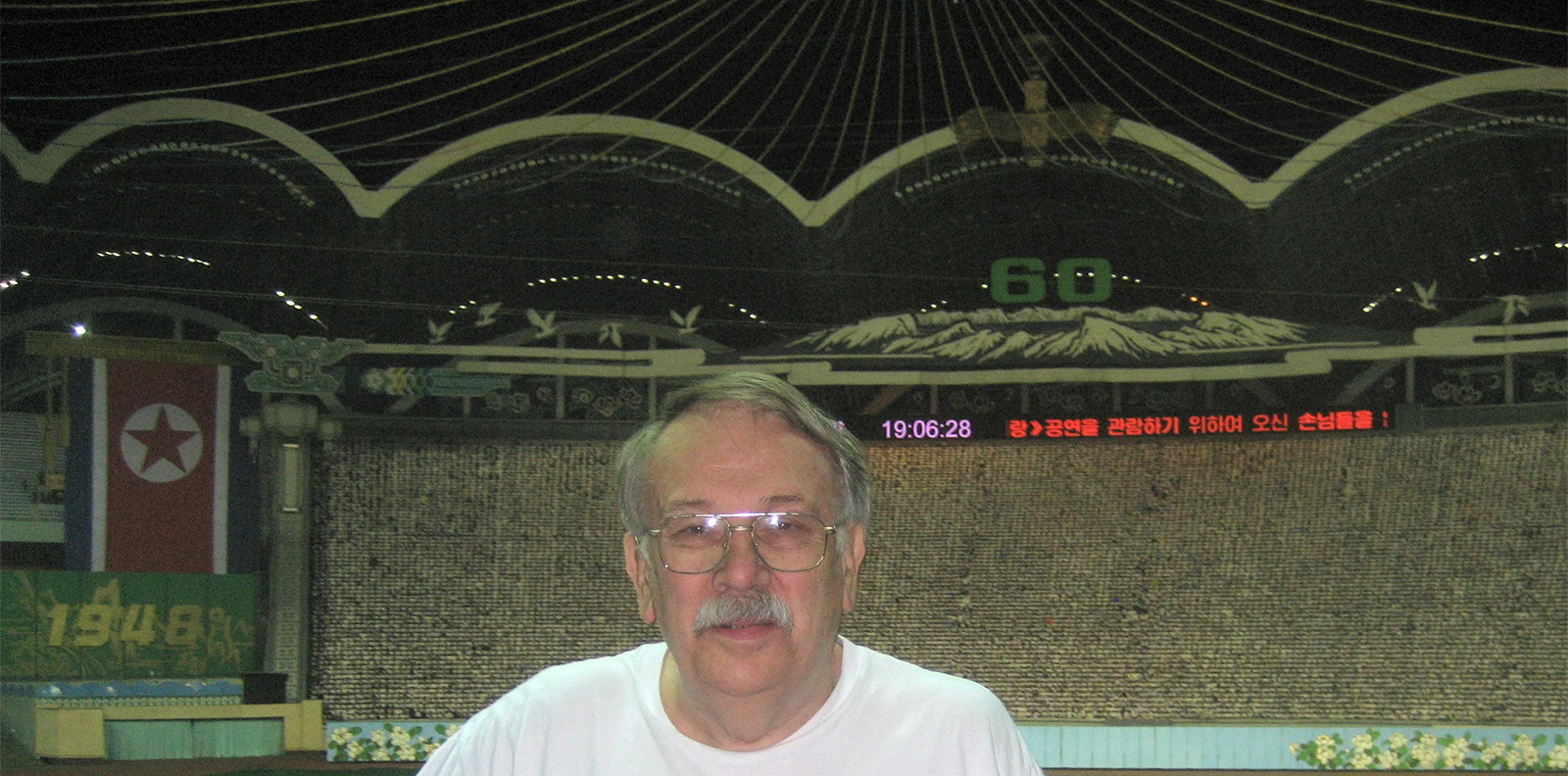

Mills attended mass games at Rungrado May Day Stadium, which he called “the most interesting sight during my five-day tour.”

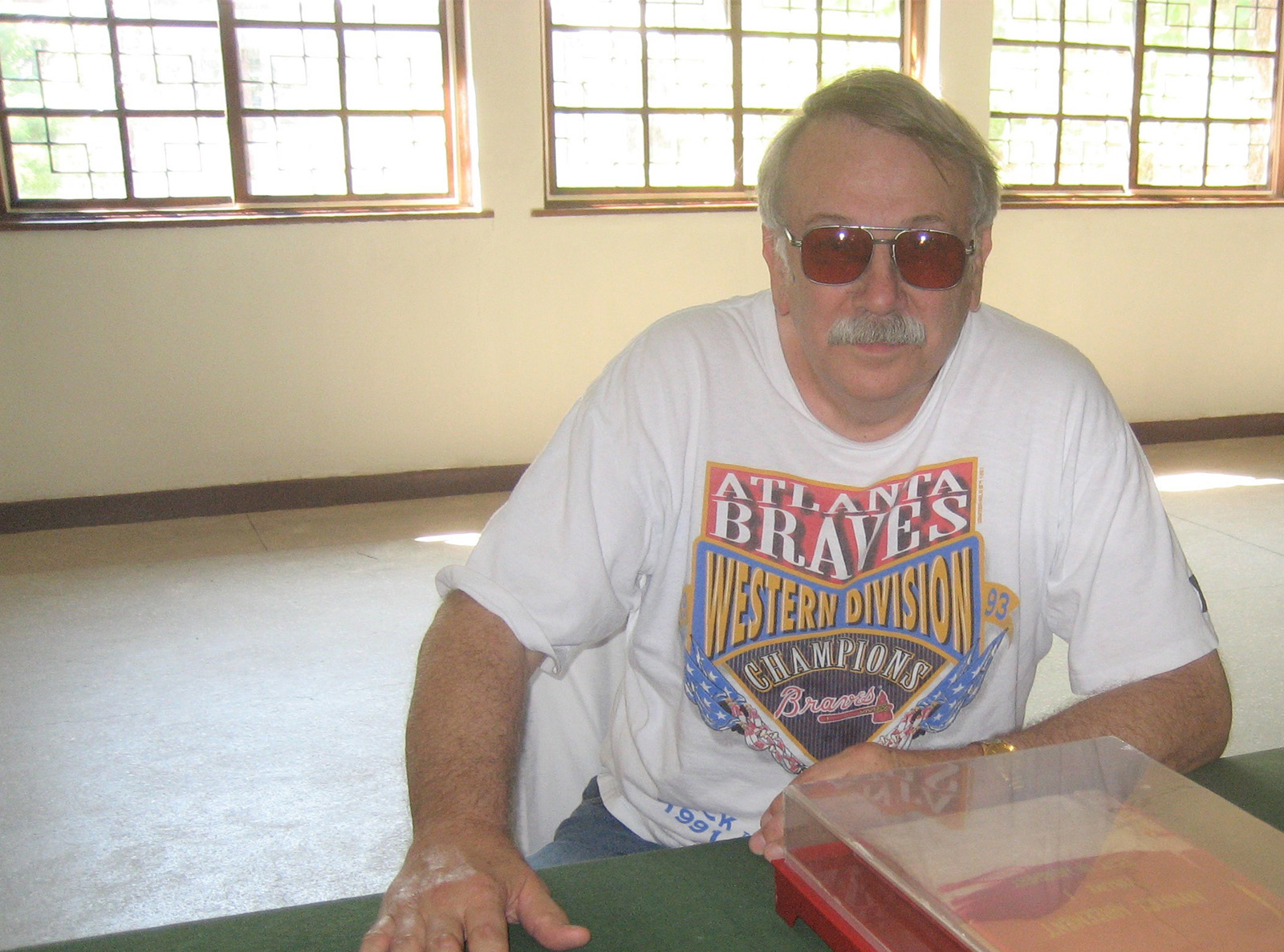

Mills’ tour also included a visit to the North Korean side of the border with South Korea.

The next morning, I got my first look at the streets of downtown Pyongyang. I was immediately struck by the scarcity of vehicular traffic. Oh, there were traffic police decked out in full regalia — just very little traffic for them to direct. Still, they stood at empty intersections as if there were the traffic flow of a typical major city. Instead, we saw occasional pedestrians and bicyclists making their way along the curbs and on the sidewalks. We arrived at the giant square where North Korea exhibits its vast array of military hardware to the world during parades. The only vehicle besides ours in the square was a pickup truck whose crew was busy picking up trash.

The next day we made our mandatory visit to the Kumsusan Palace of the Sun, the mausoleum where the remains of Kim Il Sung, whom North Koreans call their “Great Leader,” have been on public display since his death in 1994. To obtain my visa, I had to agree that I would visit this mausoleum while appropriately dressed. Most egregiously of all, I had to agree to bow before this perpetually re-embalmed body. There is absolutely no exception to this policy.

“Some halls inside the building are up to 3,300 feet long.”

I was immediately impressed by the mausoleum’s sheer size. At 115,000 square feet, Kumsusan is the largest mausoleum dedicated to a communist leader. Some halls inside the building are up to 3,300 feet long. Later, I learned that it was once the palace of Kim II Sung.

After traveling on several long moving sidewalks, I finally reached the entrance to the burial vault. As ordered, we lined up in groups of three. We were told to place our arms at our sides and walk slowly toward the heavily guarded glass enclosure that contains the body. It lies inside a clear glass sarcophagus. The head rests on a Korean-style pillow, and the body is covered by the flag of the Workers’ Party of Korea. On cue, as I had committed to doing, I made several half-hearted, perfunctory bows (read “slight nods”) as I circled the remains.

The entire ordeal took no more than a couple of minutes. I then exited through a large museum into the gift shop, which takes only euros and U.S. dollars. Then it was back to the moving sidewalks that transported me to the exit of this eerie place. As I passed by others who were coming in, I noticed how sad they looked. Those who passed by within a few feet of me always averted their eyes. No one ever smiled.

The most interesting sight during my five-day tour was the evening I spent at the Rungrado May Day Stadium — the world’s largest — where the mass games are performed. These “games” are a socialist spectacle consisting of song and dance. The 90-minute program featured more than 100,000 people who performed gymnastics, acrobatics, dance, and more accompanied by music and spectacular visual effects, all wrapped in a highly politicized package.

One of the most interesting features of the extravaganza was what the printed program called the “largest picture in the world.” It was a giant mosaic formed by individual students, each holding a book whose pages link with their neighbors’ to make one gigantic scene after another. The scenes changed as the students turned their pages. Up to 170 pages make up just a single book. The program states that 20,000 students take part in this one display alone. The mosaics ran throughout the program while other activities were performed on the huge field below.

When it was time to depart at the end of the trip, the immigration procedures at the airport before departure were more stringent than the arrival check. As one tour member muttered under his breath, “No one tries to sneak into this country.”

The flight back to China went smoothly, and it was not long before I arrived at my hotel in Beijing, where I booted up my laptop and communicated freely with the outside world again. I have visited several other autocratic countries during my years of travel, and each of these has certain irregular requirements that visitors must meet. But all of those requirements lumped together pale when compared with the rigid, absolute demands imposed upon visitors to North Korea.

I know this: I am eternally grateful to be a citizen of the United States of America.