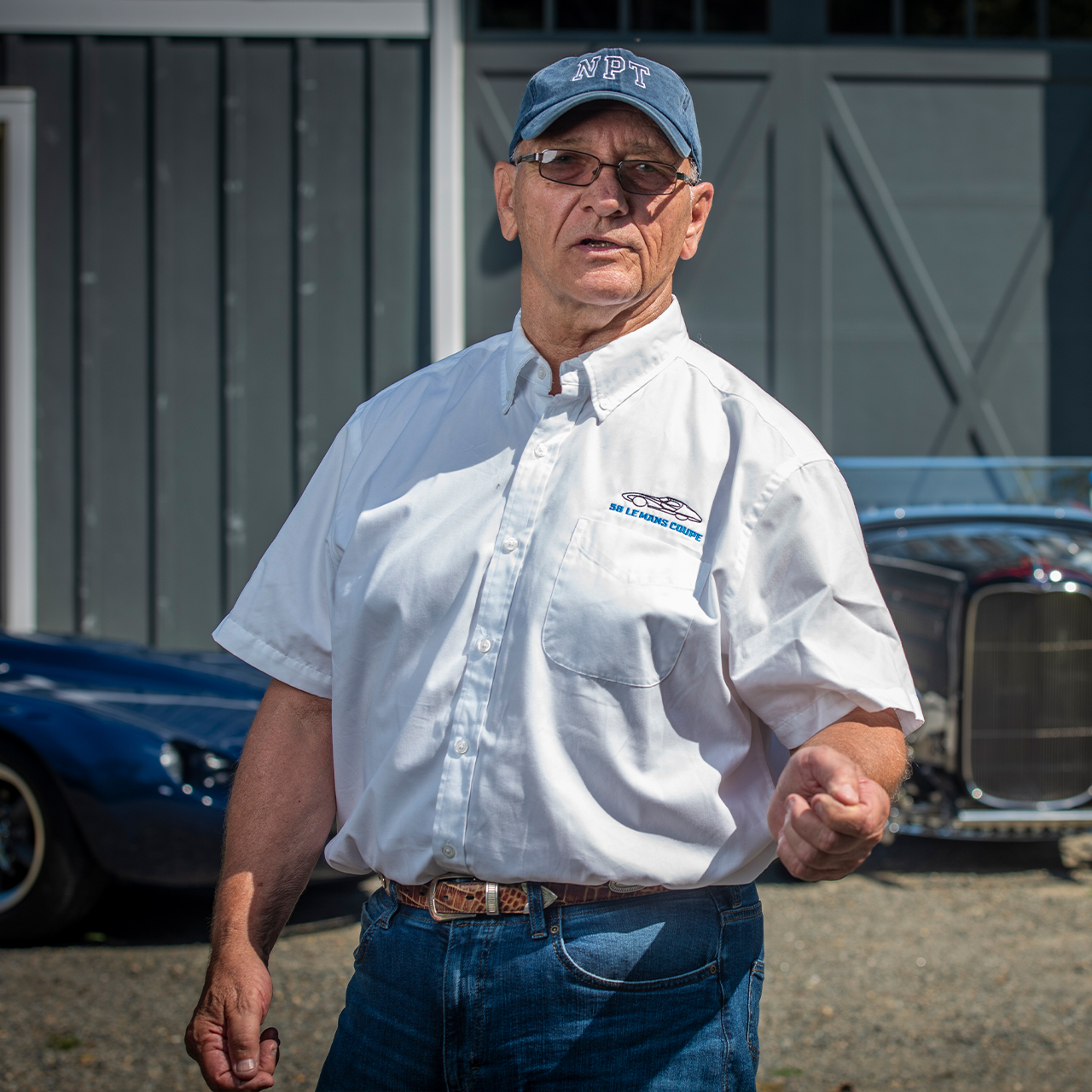

Dennis Kazmerowski, R’69, remembers the first time he saw it — cherry red and shiny, a car with sleek, swooping lines ready to make history. It was the MacMinn Le Mans Coupe, designed to bring an American team glory in the famed 24 Hours of Le Mans road race in Le Mans, France.

Kazmerowski was just 13 years old when he rode his Schwinn bike to his Baltimore neighborhood drugstore and bought for 50 cents a copy of the August 1960 Road & Track with the MacMinn on the cover.

“It was so far ahead of its time,” he said of the MacMinn.

That may have been, but it would take more than 60 years for Kazmerowski — a standout student-athlete, race car driver, and car builder whom everyone calls “Kaz” — to achieve his boyhood dream of driving one.

What would make that adventure even more special was that he and his buddies would build it from the ground up, a project that fulfilled the two lessons he lives by: Keep moving forward, and always bring your friends along for the ride.

SCHOOL DAYS IN THE FAST LANE

Cars raced through his blood from a young age. Kaz recalled how he, his twin brother, and his dad would pile into the family’s Chevy sedan and travel to the Marlboro Motor Raceway in Maryland to watch drivers like Mark Donohue, Herb Wetanson, and A.J. Foyt become legends of the Trans-Am Series.

It wasn’t just race cars he liked; he enjoyed anything that was fast. As a highschooler, he set state records in the sprint. In college, he received an athletic scholarship to play football at Richmond. After a year on the freshman team, the defensive halfback eagerly took to the varsity field his sophomore season — only to suffer a second major concussion in two years.

The coaches and doctors said his football days were over. Kaz agreed. “I hated to see it end,” he said.

He had loved the camaraderie and the thrill of playing. So Kaz rounded up guys interested in lacrosse, another of his high school passions, and started the Richmond lacrosse club, the precursor to today’s Division I team.

“We played on some of the fields over in Westham and the old stadium they have there,” he said, referring to Crenshaw Field, home of Spider field hockey. Playing lacrosse helped him reclaim the joy he had found in high school sports. “It was a way to do the things I love to do — run and have a good time,” he said.

It also was an early example of fulfilling what has become for him a lifelong mantra: “You gotta keep moving.”

“Even back in those days, I firmly believed that you just can’t sit around,” he said.

There was no sitting on the night shift at the Wonder Bread factory where he worked alongside fellow brothers from Phi Gamma Delta to help pay the college bills. He would catch loaves as they came off the line and stack them in racks.

Kaz said that when he started, it was like the scene out of I Love Lucy when Lucy and Ethel can’t keep up in the chocolate factory. “That was me. I had bread knee deep; I couldn’t catch it fast enough,” he laughed.

Kaz gets nostalgic when he talks of those times, but not because they are all in the past. Many friendships endure. He has a list of names he calls when it’s time for another reunion — he was last on campus two years ago — to be sure everyone is there to raise a glass to the days when they could get beer for a quarter at Phil’s Continental Lounge.

“You often hear the phrase, ‘Not for college days alone.’ That’s so important,” said Kaz, who says Richmond set him on the path for his life successes. He stops by campus whenever he’s in the area, watches all of the Spider sports teams he can, and hopes his grandchildren will become Spiders. “I’ve stayed in touch with so many guys I went to college with, both fraternity and non-fraternity, and it’s true — it’s not just for college days alone. College is an opportunity to connect with people, in addition to the studies. … How you handle yourself through your college days is how you’re going to handle yourself through the rest of your life. I firmly believe that.”

ANOTHER LAP AROUND THE TRACK

After college, Kaz and his wife, Karen, got into sales of skiwear — skiing being another of his athletic passions — and they eventually relocated to New Jersey to be the reps for ski shops in the five boroughs of New York City. They soon met Bob Merrill, owner of Sno-Haus Ski Shops on Long Island.

One of Kaz’s hottest items was the Apollo, a down-filled jacket by CB Sports, which Merrill sold by the hundreds.

“He was so happy you were buying his stuff,” Merrill said. “He was never pushy and always very thankful for whatever he got — and that’s why he was very well liked and trusted by everybody. You know, he would sell to competitors the same stuff they would sell to me and get away with it because everyone liked him so much.”

“The last thing you want to do is look out the side window, because you realize how fast you’re going.”

Kaz would invite 20 of Merrill’s associates to dinner and inquire about their kids by name. Once, Kaz called up Merrill as both were preparing to travel to a ski show in Las Vegas. “Bring your racket,” Kaz said. “You’re going to play tennis.”

Said Kaz of his sales work, “They are accounts who turned into friends.”

His work with skiwear in the winter meant Kaz had time and money in the summers for other passions. That included attending their daughter’s sports tournaments — and cars. As soon as he had saved enough money, he started racing in Formula Vee — a racing series featuring single-seaters with Volkswagen engines — and soon won the mid-Atlantic road racing championship.

He quickly moved up the racing circuits. At one point, Jaguar-Rover-Triumph called and offered him a car — and his choice of V-8 engines. “It was really fun,” he said.

Kaz raced for a variety of teams, including one dubbed the California Beach Boys by the professionals at Le Mans when the American crew attempted to qualify for the 24-hour race in 1990.

As one of the drivers, Kaz hit speeds close to 200 miles per hour. “It’s a blur,” he said. “The last thing you want to do is look out the side window, because you realize how fast you’re going.” What’s worse, he said, is looking out the side window and realizing a competitor just passed you going 220.

He enjoyed the opportunity immensely, he said, but from the start the team’s car had problems. It wasn’t handling well, making it dangerous to drive at fast speeds. Kaz told his wife, who traveled to France with their daughter for the trials, “Somebody is going to die in this.”

Luckily, no one did. The team did not qualify, but Kaz got another lifelong friend out of the experience. “I still talk to the gentleman who owned the car,” he said.

That level of racing — on the road 10 to 12 summer weekends a year — may be behind him, but Kaz is still going fast. At 78, he still tests a car on the track now and then and participates in vintage races once in a while. His focus, though, is now on building cars and on his family, including three grandkids — ages 13, 10, and 5 — who live 20 minutes away from his north Jersey home.

“I’d rather watch my grandkids play sports,” he said.

MACMINN REBORN

Family and cars continue to intersect for Kaz. In a recent phone conversation with the 5-year-old, granddad mentioned he needed to clean his garage. The child answered, “I’ll come over. I love to clean.”

In Califon, New Jersey, Kaz converted a small barn behind his house into a two-car garage. It’s the most recent home of the 30 or so cars he’s coaxed back to a life full of glory.

They include a 1975 Bricklin Custom with gullwing doors; a 1964 Ginetta G4 that raced at Laguna Seca in 2018; and a 1987 Corvette GTP that appeared on the cover of Sportscar International in 1990.

“I can’t leave anything alone,” Kaz said. “Even Karen’s Jeep has different wheels and tires.”

Most recently, he’s received accolades for the buildout of the 1958 Le Mans Coupe. Renowned designer Strother MacMinn created the car’s aerodynamic shape. He designed the body in hopes that an American team would build it out with off-the-shelf parts — transmission, engine, etc. — and take this country’s first win at the 24-hour Le Mans.

Only six fiberglass bodies of the MacMinn coupe were ever produced. Only two had previously been built out; the red car on the front of the 1960 Road & Track now lies in hundreds of pieces after its driver sent the car careening over the edge of a California highway, and the second one is nowhere to be found.

Since he was a boy, Kaz wanted a MacMinn. When he learned there was a fiberglass MacMinn body baking in the California sun, he had to buy it.

He called up John “Chip” Fudge and asked him to be a financial partner. The men had met a decade and a half previously through a mutual friend who crewed on the Le Mans Beach Boys team. “He trusted me, and I trusted him,” Fudge said. “That was the start of an amazing ride these last five years.”

“I called seven friends to come over to look at it and said, ‘Can we build this?’

Two of them left right away, [saying] ‘No, I don’t want to be part of it.’

And the other five guys were invaluable in their help.”

Kaz trucked the MacMinn body from California to his New Jersey barn.

“The California sun had taken its toll,” Kaz said. “It’s light fiberglass, so it started to sag here, it started to sag there.” But he and Fudge had made the investment, and he had to figure out what to do. “I called seven friends to come over to look at it and said, ‘Can we build this?’ Two of them left right away, [saying] ‘No, I don’t want to be part of it.’ And the other five guys were invaluable in their help.”

To say it was just a shell doesn’t do the project justice; there were no doors cut out of the fiberglass, no windows, no hood. It was an idea of a car more than it was a car.

When you restore an automobile, you take it apart and put the pieces back where they came from. This was not restoring; it was building. “When you build a car, you’ve got to decide where all these pieces go,” Kaz said. “Sometimes they work, and sometimes they don’t.”

He studied the schematics printed in Road & Track starting in 1958, trying to stay true to the original vision by using period parts when possible. But the body was so thin that when they put it on the frame, it sagged 2 inches. All the headroom was gone. “It was so bad I couldn’t get in, and I sure as hell couldn’t get out,” he said. So they had to reinforce the original fiberglass, which was the thickness of two layers of T-shirt material.

He’d drill a hole, only to decide it wasn’t in the right place. Then he’d have to patch it and try it again. When it came to the headlights, he didn’t want to cut into the hood to mount them. So he solicited advice from Peter Brock, designer of the Shelby Cobra that won the 24 Hour Le Mans GT class in 1964. Brock said, “Kaz, just put the lights down in the grill.” So he did.

“[Kaz] trusted me, and I trusted him. That was the start of an amazing ride these last five years.”

Kaz could do only so much in his converted barn since it had no car lift. Enter Bill Lauricella. Years before, Lauricella had sought out Kaz while working on a Fiberfab Centurion, a fast, flat body built in the 1960s. “Any question I have, I know I can call him anytime, and he’s either done it or been there or knows somebody who could help you out,” Lauricella said. “And more than likely, he’ll be standing in the rain watching a lacrosse game.”

Now it was time for Lauricella to repay the favor, and they moved the MacMinn to his Corvette showroom and shop in Belvidere, New Jersey.

“He’s the kinda guy who would do all this stuff during the day, family stuff,” Lauricella said. “And at night, he’d be there until midnight working on the car himself.”

It took more than 3,000 hours over 20 months with a host of friends to build out the MacMinn. A friend offered a motor. Another said he’d paint the car. The collaborative process was chronicled on the blog Undiscovered Classics, and the car started to receive accolades even before it was complete.

For Kaz and Fudge, the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance would be the ultimate showcase for the MacMinn. The car show accepts only about 200 entries a year worldwide, and in 2023, the MacMinn was one of them.

They had a deadline. Now they needed a paint color.

For 60 years, Kaz had in his head that the car should be red like on the cover of Road & Track. Fudge said it was the only aspect of the car on which they disagreed. “It can’t be red,” Fudge said. “I hate red.”

So Kaz picked a color called Black Cherry Metallic used on Pontiac dashboards in 1955. It looks black until the sunlight hits it, when it shimmers like rootbeer. It was beautiful. And it was finished only days before Pebble Beach.

“The paint was still drying in the truck on the way out to California,” Kaz said.

When he and Karen drove onto the green in Pebble Beach, they turned heads with the body’s long aerodynamic lines and the throaty rumble of a 283 cubic-inch 1957 Chevrolet Corvette V-8 engine. It was a dream come true, bringing the car to the home state of MacMinn, who taught generations of automotive artists at Pasadena’s ArtCenter College of Design.

The whole family was there, as were Fudge and his wife, Shannon. Kaz’s youngest grandson helped granddad shine it up. Bob Gurr, who designed everything from Disney’s monorail to The Haunted Mansion, was so excited to see the car by his former ArtCenter professor that the 92-year-old bent down and kissed it.

From the Monterey Peninsula, the MacMinn traveled south to the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles — which Kaz believes is how Jay Leno first saw it and invited them on his YouTube show Jay Leno’s Cars.

In the episode, the former late-night comedy host gushes over every aspect of the car, from the immaculate engine bay to the striking side scallops. And then he asks to take it for a spin “around the block.”

Before the episode, the car had 7 miles on it — just enough, Kaz said, to test it out so it wouldn’t “blow up or catch on fire” at Pebble Beach. Now he hoped it wouldn’t blow up for Leno.

As they climbed into the car, Kaz seemed a little distracted; you can see it in the video. Leno noticed too and commented to Kaz, “Are you listening to me?”

“I said, ‘Jay, I’m trying to hear what’s falling off,’” Kaz laughed. “Nothing fell off. It was just a great day.” And how many miles did it have after Leno took it around the block again and again? “A lot more than 7.”

Kaz calls his appearance on the show “the epitome of my car building.”

The MacMinn went on in 2024 to win the chief judges award at the Amelia Concours d’Elegance in Florida and the chairman’s award at Eyes on Design in Detroit. The car now is part of Fudge’s private collection in Oklahoma.

Kaz is back in the barn, working on a one-off Porsche he’s completely redesigned. He dropped in a 993 3.6 liter air-cooled engine and plans to race it. When he does, he expects this car will also be showcased by automotive magazines.

And then there’s the Ocelot, a car project that finds Kaz and Fudge partners again. The car has a story worthy of a grand restoration — the only existing body by renowned auto artist Ken Eberts, stolen in the 1960s, found 60 years later 15 miles from Eberts’ home. Fudge describes it as “a wedge of cheese on its side, with wheels.”

“I used to look for this stuff, but now they find me,” Kaz said. His only regret is that it’s happened so late in life. There are so many more projects he hopes to complete.

There are also more friends to make. “You’re only as good as your friends — I honestly believe that,” he said. He works hard at it, keeping a list and being sure he calls or emails each one regularly. “I’m so fortunate I have tons of friends.”

While working on the MacMinn, he said he often wondered whether the reality of building the car would match the imagination of building it. “I can honestly say it has,” he said.

“It’s been a good ride.”

Additional photos courtesy of Jay Leno's Cars.