“I can’t believe we’re here,” I say to two of my traveling companions, sophomore Eden Burrell and first-year student Katie McCrary. The three of us are all students at the University of Richmond. We, along with three other students and four of our professors, are about to embark on a real-life treasure hunt like something out of an Indiana Jones movie.

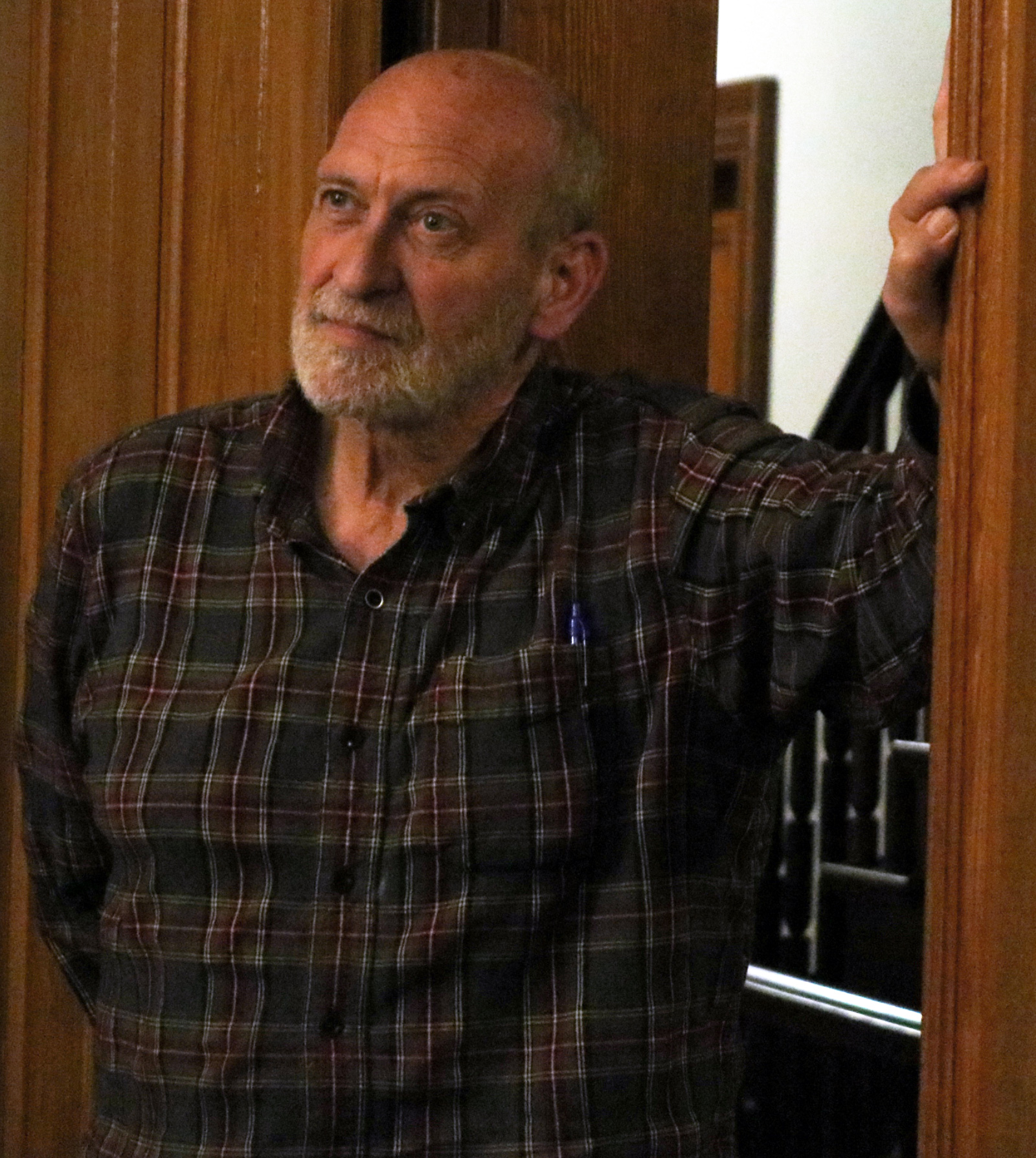

This sandy hillside is just a half-mile east of Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village — the last active Shaker community in the world. The village is a vestige of the past. Standing on the porch of an unadorned white house is Brother Arnold Hadd, the village’s cook, custodian, sheepherder, and elder. He’s short and sturdy with soft features, dressed in a plaid button-up flannel and steel-toed boots. Brother Arnold lives with Sister June Carpenter and Sister April Baxter — the only three remaining Shakers.

The Shakers are a restorationist sect of Christianity that emerged in the mid-1700s in England. Mother Ann Lee, an English mill worker and mystic, emigrated to North America in 1774 with a handful of believers and settled at Watervliet, right outside of Albany, New York. After her death and the wildly successful missionary tours she went on throughout New England, converts established some of the earliest Shaker communities. At their peak in the middle of the 19th century, there were several thousand U.S. Shakers living in more than 20 communities that stretched as far as Kentucky and Indiana. The dwindling of their numbers throughout the 20th century led to the dissolution of all but one: Sabbathday Lake.

Shakers are revolutionaries, and the village is their version of a heaven on Earth rooted in simplicity, tradition, communalism, and celibacy. In an unusual period almost 200 years ago called the New Era, Shaker visionaries received revelatory communications about an outdoor Passover feast that would happen twice a year at special sites. The grounds were elaborate, surrounded by spiritual orchards and vineyards. Sabbathday Lake’s worship feast ground sat atop a hill west of the village, and at its center was a fountain. The fountain wasn’t a material fountain into which you could dip your toes. It was a spiritual body of water where you came to give your soul to the mists of holiness. On summer days, the brethren and sisters hiked in procession up the pathway to bathe in the spiritual holy water and partake in songs and marches.

They believed that the spiritual water erupted from a 7-foot, physical marble monument they carved and inscribed with a revelation. More than a dozen Shaker communities built worship feast grounds with similar fountain stones in the mid-19th century. As the communities declined, almost all of the stones were lost or destroyed either by vandals or Shakers themselves. There is only one unscathed stone known today — now part of the collection of the New York State Museum. The Sabbathday Lake Shakers are said to have buried their stone long ago at a secret location off the hillside of the feast ground. We are here to uncover it.

I don a bright orange safety vest and sling camera equipment across my shoulders. The leaves are just beginning to change, and it’s chilly, especially for a Southerner like me. But I’m kept warm with fiery anticipation, and one question dawns in my thoughts: What would it mean to unearth this stone — a monument which stands at the center of a crossroads in Shaker history?

“Are you sure this is the spot?” New York-based archaeologist Matt Kirk asks Doug Winiarski, the Richmond professor of religion and American studies who is leading this trip.

“That’s what the radar showed,” Winiarski responds.

Winiarski — we all call him by just his last name — is a humble man, and his curiosity about religion runs deep. He’s spent the last few years digging through archives, journal entries, maps, and village sketches that catalog Shaker history. He’s also spent hours with Brother Arnold, attending celebrations and foraging through the village’s library collection. Last year, Winiarski met with geoarchaeologists from the University of Maine and conducted a ground-penetrating radar survey at the hillside. That survey revealed a 7-foot anomaly buried 6 feet down at the spot where we are now.

Our dig group of 10 gathers at the top of the hill. We six students all met together for the first time just yesterday chatting over convenience store food at the airport in Richmond. Half of us are religious studies students, the other half archaeology, geography, or environmental studies. I’m here as a student journalist. We are a wild mix — perfect for this trip.

“Timber!” someone yells in the distance as an excavator knocks down young trees at the dig site — a small square just a few yards in length and width.

I’m down the hill as Eden, senior Gloria Kroodsma, and Winiarski’s son — Nathan, a 2025 graduate who majored in geography — hand-drill into the tallest trees with a borer that looks like a giant screw with a handle at the end. Eden wears a navy blue hat with “Tree Inventory” embroidered on the side — it’s fitting for the occasion. Taking turns twisting the handle with all of their body weight, they yell “Your turn!” to each other when the borer gets stuck. They’re burrowing into the trees to extract a thin sample of the core to determine the tree’s age and growth. The extracts may show what the hillside looked like when the stone was buried and help us discover why the Shakers chose to bury the stone here.

I walk up the hill and spot Winiarski, Katie, and two other students, sophomore Seavaun Agmon and junior Kaylee Wyrick. We’re about one hour in, and they’re standing arms-crossed and eyes-widened as the excavator digs out buckets of sandy soil. After a few feet of soil are removed, we jump into the pit to examine the soil layers and dig our gloved hands into it, hoping to uncover a sliver of the marble slab.

At four hours in, we’ve just finished our picnic lunches, and all of our eyes are locked on the ditch. It’s the third one the excavator has dug — the first two 8 feet deep and nothing but sand and rocks. We all sit frozen on the hill with a perfect view of the ditch. We’re afraid to move, afraid we might miss what we all hope to see. Doubt starts kicking in.

“What if we don’t find it?” I ask Kaylee. “I mean, it’s got to be there, right?”

After each new ditch comes up empty, the excavator returns the hill of disrupted soil to its hole. I can see the scars left on the site — the ditches dug just feet away from each other, one pointing north, another west. It’s hour five, and the excavator starts digging again. I repeat in my head, “This has got to be the one.”

“What if we don’t find it? I mean, it’s got to be there, right?”

Elizabeth Baughan, a Richmond classics professor and the professional archaeologist on the trip, says, “Look at this.” She’s pointing to the side of the new pit, where just a few feet are dug out. A few of us peek into the ditch. I see distinct ribbons of dark, almost black soil foiled in layers between the brown sand we are familiar with digging our hands into.

“What is that?” Katie asks our professor as bits of charcoal stain the tips of their gloves. Baughan explains that it’s a disruption that shows that, at some point, the soil was unearthed and replaced. The charcoal is evidence that a fire once burned in this spot.

The ditch reaches 8 feet deep, and the rattling of the excavator ceases. Matt and Katie continue to map the site in pencil on a sheet of grid paper. Winiarski stands hands on hips, sunglasses resting on the brim of his baseball cap, staring into the pit. There’s no stone there.

“I think we have to call it, Doug,” Matt says. “If it was here, we would’ve found it.”

Back at the village, the sun is just starting to set, and Winiarski pulls open the door of the dwelling house. Two staircases lead upstairs, one on each side, and the wooden floor creaks with each step. We walk into a dimly lit room upstairs where the walls are adorned with portraits of Shaker icons. We sit down with Brother Arnold and village director Michael Graham. Sister April Baxter, the religion’s most recent convert, and close members of the surrounding community join the discussion.

Earlier, I’d wondered what it would mean to find the lost stone. Now, a new question is in my thoughts: What does it mean to hunt for the lost stone and come up empty?

Brother Arnold committed to Shaker life 47 years ago, and now, the religion stands on his shoulders. When he joined, he never expected to hold such a high role in the community, let alone be considered the spokesperson for what many call a dying religious community. For Brother Arnold, the hunt wasn’t about finding a lost remnant of a history, but a reminder of hardship, labor, and religious devotion to Christlike living.

Still, we’re all surprised when he tells us that he believes that feast ground worship happened, but he wouldn’t have bathed in mists of imagined holy water if he were a 19th-century Shaker. He also believes that the grounds led to the steep decline of believers and converts in the late 19th century. I felt a wave of dismay in the room.

Sister April raises her hand. She’s a short woman dressed in a purple cotton shirt with thin glasses sitting on the bridge of her nose. With a strong voice and assertive tone, she asks why we went hunting for a remnant of a history that should be forgotten.

The next morning, the air is crisp. Shakers call their Sunday worship “meeting,” and it’s held in an open room in the upstairs of the dwelling house. The meeting room is lined with wooden benches, not pews, on each side of the room. The room is sparse, and morning light peeks in through the window overlooking the sheep farm.

Five of us are here, while Gloria is up on the hill with the professors flying a drone to take aerial photos of the village and feast ground site.

I sit down on the left side of the room. In Shaker practice, genders are separated. Women sit on the left facing the men on the right. The meetings are open to the outside community, and about 30 people line the benches this morning — some who drove hours at dawn.

A calm silence fills the room until Brother Arnold — dressed in a black vest with a white cotton long-sleeved undershirt and baggy pants that puddle on his work boots — walks in. The meeting opens with passages from the Old Testament and New Testament read aloud by Brother Arnold, Sister April, and the village’s beloved retired librarian, Larry. Between each passage, I stand up and sing along to Shaker hymns that Brother Arnold chose the night before.

“I know they felt worry, but the hunt wasn’t just about finding a lost remnant of history. It was the new connections we made and the thoughtful conversations we had.”

Everyone sits quietly, and Brother Arnold starts to speak. It seems like an improvised, less devotional version of a sermon. He recalls the biblical story of Jacob’s ladder from Genesis. The ladder is a connection between heaven and Earth, Brother Arnold says, and reaffirms God’s presence in a life consumed by worry. It felt comforting for us students who had traveled so far but come up empty.

Following his lesson, we all sit silently in a ritual of thought and contemplation. After a period of silence, Shaker and community members begin to stand to speak, in keeping with Shaker meeting tradition. They pick up on Brother Arnold’s theme, sharing anecdotes and feelings of worry from their own lives.

After a while, Brother Arnold rises slowly from the bench across the room. “We have a group of students here,” he says, “for an archaeological dig up a hill from the village, and they came up empty-handed. I know they felt worry, but the hunt wasn’t just about finding a lost remnant of history. It was the new connections we made and the thoughtful conversations we had.”

Before getting back on the road to visit Shaker sites nearby in New Hampshire, we meet Brother Arnold outside. “Come back and visit,” he says, giving each of us a hug. We grab a few bags of apples from the village’s shed and hit the road, our minds turning over completely different questions than the ones we arrived with.